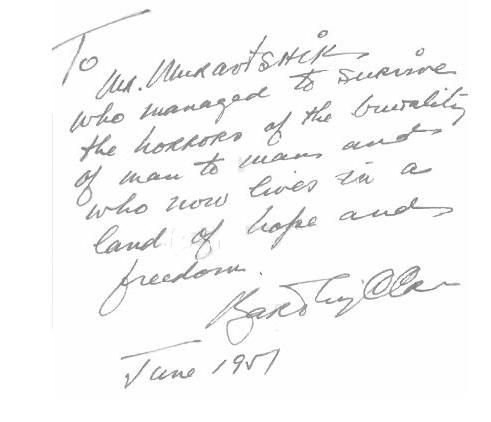

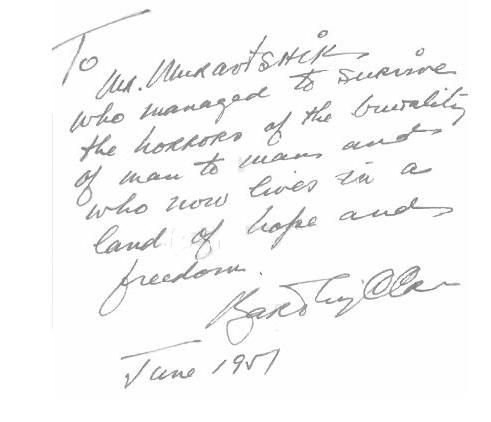

Bartley Crum's dedication on his book, that he gave to the author

| Previous | Table of Contents | Next |

Between Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur, during the Ten Days of Repentance, my uncle's family and I left Levov, heading to Poland. We arrived in the city of Bitom in Shelezia. The German residents of the city, as well as the Polish of German origin, left the city, like all Germans who lived in west Poland. I notified my family in the United States that I am in Shelezia, and they sent me some money for living.

On those days, many dealt with trading with German currency, the Mark. One day, local Polish robbed one of the banks in Shelezia and smuggled the Marks to Germans, where, of course, it was legal tender. I have already decided not to be involved in commerce. On the other hand, I felt a strong urge to volunteer for public work, to be active for the community.

From Bitom, the "Union" headquarters sent me to Lodz, where a "Kibbutz" of graduates of the "Zionist Youth" movement and "Akiba", was established on those days. There I met again Hillel Zeidel, of the leaders of "Akiba". I knew him from the Vilna ghetto. Later he found himself in a concentration camp in Estonia, and there he was rescued. I knew him well, and he gave me 5,000 Zlotty, from the money that came from the Joint in America, for distribution among the movement activists. This was the first time that I got money for my work with the movement. Till then, all my activities were voluntarily, and I was quite surprised to be given money for public work. I was given the task of gathering youth in Kibbutzim for transferring them to port cities of Italy, France and Romania, on their way to Eretz Isroel. This method was called "Aliya Bet". Practically we dealt with "The Escape". In addition, we had to look for Jewish children and youngsters in monasteries, where their parents, on their way to death camps, left them.

In December 1945, I traveled together with my friend Romek to Gedansk, on a cargo train, for preparing a location for a Kibbutz that should be close to the Baltic Sea. Later a "transit Kibbutz" had been setup in nearby Zopot. Gedansk had totally been destroyed by the Soviet army.

Right after the war, all distinctions between the various movements were eliminated, and we established one general movement, with no difference between left and right, the "Union" movement, which was the dominant Jewish movement in Poland. The "Union" movement stood for one single idea - immigration in Eretz Isroel. Already before the war broke out, I was a member in the "Zionist Youth", quite familiar with the differences between the various parties. But most of the youth did not know Hebrew, and was quite far from Zionism.

At the fall, we met for the first time with a delegation of soldiers of the Hebrew Brigade, in army uniform. I was very much impressed by the Brigade soldiers, and I felt excited to see the blue Star of David carried proudly on their sleeves. Of course, I remembered the yellow Star of David that we were forced to wear on our chest and back, in the Vilna ghetto. Among the Brigade soldiers, I met Mara Entin, a member of Kibbutz Nitzanim, of Pinsk origin, and he gave me regards from my sisters in Eretz Isroel.

In December, it has been decided to transfer the Lodz Kibbutz from Poland to Germany, via the Carpathian Mountains. I was assigned to head the Kibbutz. Our exit was set to Christmas night, with the assumption that the border guards will be celebrating and drunk. It was in the middle of winter and a lot of snow gathered on the roads. The aim was to walk by foot, with rucksacks on our backs, containing minimal equipment and necessary stuff, via the high Tatar Mountains, to the first Czech train station which is adjacent to the Polish border.

Before leaving Waldenburg, I was given a 2-year old baby girl, without parents, whom I handed to one of the young man to carry with him across the mountain. And here, to my surprise, I saw the baby lying on the snow. Probably, it was difficult for him to carry his belongings and the baby, and he put her down on the snow. Of course, I took the baby and we crossed the border in peace. Obviously, the baby arrived in Eretz Isroel, but I never succeeded in tracing her, although I would want very much to meet her.

We arrived at the top of the mountains and from there to the train station that took us to Prague. After a few days in Prague, we crossed the German border, at the Bavaria district, and arrived in the town of Leipheim, to a camp that in the past served the German army.

I stayed in Germany about a half a year. I received some money from my uncles in America, and - without my asking - they renewed my invitation to America, that they sent me before the war. But I was determined to go to Eretz Isroel. First, because of my family, my two sisters who lived in Israel, but no less, because of the Zionist education that I have been given in my childhood, the final goal of which was to immigrate in Eretz Isroel. In Leipheim we were called "the displaced", and the authorities gave us certificates to this affect.

I had regular contact with my sisters in Tel Aviv, and I wanted to get to Eretz Isroel, as early as possible. I gave up the immigration in the United States.

The camp was administered by UNRRWA, and I was elected to the camp management and to the national council of the survivors, in Munich. I personally did not live in the Kibbutz; I lived with my uncle and his family. In the camp, there was a self-service restaurant, as customary in the west. But, to most of the camp residents, all of which came from concentration camps, this reminded them of their stay in the camps and they opposed the self-service method. They demanded that food products be distributed and they will cook for themselves. They also didn't like the food, and claimed that not all the food that is due to them indeed comes into their mouths. Of course, there were neither financial nor technical possibilities for self-cooking, and the camp residents declared a hunger strike. The strike hurt the UNRRWA people and indeed the food had improved, but, due to the circumstances, the central self-service restaurant could not be eliminated.

Most of my time, I dedicated for persuading youth to immigrate in Eretz Isroel. Although I was a member of the "Union" party, when meeting with the youth I never participated in political debates, as far as the political structure in Eretz Isroel is concerned. At that time, MAPPAI - the Eretz Isroel Workers' Party, was the dominant party in Eretz Isroel.

Many emissaries from Eretz Isroel, representatives of all parties, came to the displaced people camp in Germany, for hunting supporters for their parties. Most of the emissaries were of the Eretz Isroel Labor Party (Mappai), and a few were of the Haopel Hamizrachi (religious) party. They worked in educating the youth, but divided the "Union" movement. I was supposed to defend the "Union", not only in Leipheim, but also in all displaced people camps in the American zone. Together with me worked Haim Michaeli, from Lachva. He fought within the Red Army, at the end of the war he deserted, and later came to Eretz Isroel, where he occupied himself with agriculture. Both of us used to visit the camps with an attempt to persuade the youth to immigrate in Eretz Isroel.

Years later, Abraham Cohen, Israeli secretary of Disabled of the War Against the Nazis, reminded me of this. I felt joyful when he maintained that I persuaded him to immigrate in Eretz Isroel. I have no doubt that there are many more like him. My knowledge of the Hebrew language helped me to be in touch with the emissaries from Eretz Isroel and with the Eretz Isroel office in Munich, where my friend, later on my wife, Chayah Fischer worked.

In December 1945, the United States president Truman appointed the lawyer Bartley Kram to the Anglo-American Inquiry Committee on Palestine. This committee, among its other tasks, visited the displaced people camps in Germany, and investigated the Jews' situation in Germany.

At the beginning of 1946 (January-February), the committee visited our camp, and the emissary Amram from Lahavot Habashan called me to testify before the committee. I did not know English but spoke Hebrew, and Judge Rivkind from the United States (persident Truman's advisor for displaced people in Europe), translated my testimony from Hebrew to English. Later on, the committee member, Bartley Kram, published a book, which was translated into Hebrew and called "Behind the Silk Curtain".

From the questions that my friends have been asked by the committee I understood that, practically, they want to understand why the youth that survived the holocaust wants to immigrate in Palestine and doesn't want to stay where they lived before the war. Why the Jews don't want to assimilate or immigrate in other countries and prefer to immigrate in Palestine. At that time, government allowed Jewish refugees to return to their former places, or to immigrate in countries that opened their gates to refugees. By the way, for me personally the quota limitation has been annulled and I could immigrate in the Unites States. I told the committee my life story, and through my story, I succeeded in making it clear to them that even if I would want to assimilate, I wouldn't be able to do so, because the Polish society did not want to accept me. I told them that, as of my childhood, I studied in elementary and secondary schools only among Jews, because I was not accepted into schools were Polish studied. I continued and told them about my study in the university, and about the notorious "Benches Ghetto" and the beating of Jewish students by Polish. Also among the partisans, I told them, there was anti-Semitism, and the Christians did not accept Jews as equals among equals. Judge Rivkind indeed mentioned Polish partisans, but I was among Russian partisans and the difference was enormous, because the Polish were not satisfied with anti-Semitism alone, they simply killed Jews. I concluded my testimony saying that my life story is practically the story of all Jews of my age who were lucky to survive the inferno.

At the end, I expressed my wish to be with my close family, after my entire family has been murdered, and rebuild my life in Eretz Isroel, near my sisters.

My testimony has been published in the paper "Forwerts" which appeared in New York, in Yiddish, and it served for an interpellation in the British parliament, by Sidney Silberman, a representative of the Liberal Party. Later on, the committee recommended that 100,000 certificates be granted to the displaced. I prefer the term "displaced" rather than "refugees" or "survivors", as they used to call us then in Eretz Isroel. I felt proud that my testimony before the committee contributed to its decision.

In 1951, Bartley Kram the author of the book "Behind the Silk Curtain" arrived in Israel, on a business trip. I met with him and showed him his book that was translated into Hebrew, and was given to me as a gift by my friend Baruch Egozi who was an accountant in Jerusalem. He showed interest in my situation and wrote on the book a dedication in English "To Mr. Moravchick, who survived the atrocities and brutalities of men to men and lives now in a land of hope and peace".

In March 1946, I participated in the General Zionists convention that took place in Paris. I had no visa to France, but with my partisan experience, sneaking the border to France seemed like a children's game to me.

Bartley Crum's dedication on his book, that he gave to the author

We crossed the border with the help of a German guide, near Saarbriken. The permit to stay in Paris I received later, thanks to one of the religious organizations. After a two-week stay in France, I returned to Leipheim. When I arrived in Leipheim, I received notice from my sisters that the Palestine mandate government granted me a certificate for immigrating in Eretz Isroel. My brother-in-law, Aharon Frayerman (Cheruti), worked for the border control of the Mandate government and knew one of the directors, through whom he succeeded in granting me the awaited certificate.

Germany after the war was under military rule; an exit permit from Berlin was required for exiting Germany. Obtaining such a permit was a long and cumbersome procedure. Therefore, my certificate was deposited at the British embassy in Paris. By the end of July, I traveled to Paris and there the British visa to Palestine was stamped in the "passport" that was issued for me in Munich.

The Jewish Agency in Munich, printed with a typewriter all my personal details and attached my photo, practically, this was a sort of passport of the Jewish state in the making. I handed this document to the "Massuah" museum.

| Previous | Table of Contents | Next |