| Previous | Table of Contents | Next |

At my childhood, David-Horodok was a typical Jewish small town of the Settlement Boundary*). Like most East-European Jews, most Jews of David-Horodok originated from West-Europe, and, like in all Shteitlach, the Jews dwelled in the center of town, and the non-Jewish dwelled at the town outskirts. A stranger who would arrive in our town would think that this is a meticulous Jewish town.

Paved roads did not exist in the Pollese district, in those days, and the connection between our town and the adjacent towns had to be by horse carriages or by boats, and later on - by steam ships. The main means of transportation were the many rivers, all of which flew into the Pripet river, which flows into the Dnyeper, that flows into the Black Sea.

The railroad station was located at about 23 kilometers from David-Horodok. To get to the station, one had to travel on a horse and carriage through the adjacent town Lachva. During the summer, it was necessary to cross the river Pripet on a ferry that could carry four carriages. Another railroad station of a train that traveled from north to south was about 30 kilometers from our town, at the banks of the river Horin, adjacent to the town of Stolin, which was famous thanks to the Stoliner Rebbe. To this station, one could get by carriage, or by steam Ship. The connection with Pinsk, the district town, was also by a steam ship, in a journey that took 16 hours. (Subsequently, a 120 kilometer paved road was constructed between Pinsk and our town, which made it possible to travel only 2 hours by bus). Traveling on the rivers was more convenient than with carriages, but it was more dangerous. Quite often, it happened that in winter, the thin ice on the river cracked and carriages with their passengers sank in the frozen water.

At the spring and fall seasons, especially in years with a lot of rain, the rivers would overflow and carriages with their passengers would sink in the swamps, requiring a great effort to rescue them. During winter, we used to travel in special winter carriages, sledges. Some times, due to difficulties in transportation, our small town was cut off from the outer world.

Most shops and businesses in town were owned by Jews, who traded with the town's Christian inhabitants and with inhabitants of the neighboring villages. The villagers would come to our town to sell their merchandise: eggs, chickens, timber, and bush fruits. Most of the Jews were merchants, some of them were craftsmen - tailors, shoemakers, locksmiths, some worked in forestry, transportation on sea-craft and fish trade. Transportation as well as commerce was mostly in the hands of Jews. The carriage drivers (Baal Aggoles) were Jews, some of them worked in transporting passengers between towns, and some in transporting cargo in town. And, of course, there were Jews who did not work at all.

Most of the Jewish population in this area was religious (not orthodox). Some were secular-traditional. In our town, there were five synagogues. One of the synagogues was the Stolin-Karlin Chassidim Shtiebel. All the Jewish stores were, of course, closed on Sabbath. The elder and adults went to the synagogues, while the youth, who were mostly secular, went bathing and floating boats on the river.

On Saturdays and on holidays I used to go to the synagogue. Sometimes, when I came late to the Torah reading, my father never insisted that I should start the prayer from the beginning, but he was always strict on explaining to me the meaning of the words of prayers and of the Torah weekly portion. Till today I remember verses and phrases of the weekly portions of Torah and the prophets, as well as cantor melodies, thus the Jewish term of "Girsa Deyankuta" (knowledge acquired in childhood) was realized in me.

At home, we observed Kosher, but when I arrived in Vilna I also ate in non-Kosher restaurants. My brother, who was a smoker of cigarettes, never smoked at home on Shabbat; neither did he smoke on Shabbat at locations where people could see him. It is not that we were hiding from our parents, I am convinced that they knew what we are doing, and it is just that we didn't want to hurt their feelings or embarrass them in any way.

It must be assumed that the local orthodox Jews, did not like the way of the conservative and non-religious, to say the least. But, and it is important for me to stress this fact - the relations within the Jewish community, between the orthodox, the traditional and the non-religious, were of tolerance and mutual respect. Practically, this kind of symbiosis led to friendly relations between the various groups. I wish that such tolerance will exist within the State of Israel.

When I reached the age of 9, my father began to teach me the reading of the Haphtarah (the portion of the prophets that is recited every Sabbath), as he did with my older brothers, Velvel and Yossel. So, I was privileged to be called up to the Torah and to recite the Haftarah at the age of 10. When I reached the age of 13 (Bar Mitzvah), father did not send me to a Rabbi to teach me how to put on the Tefillin, but he taught me himself. He did not insist that I practice all the Mitzvahs (commandments). Still, during my entire life, I maintain our tradition and, since the age of 13 till today, I fast on Yom Kippur.

A few words, regarding the relations between Jews and gentiles, in our town. As children, we didn't quite understand what is the meaning of anti-Semitism. Our parents maintained good relations with the gentiles. Many of our store clients were Christians who used to buy linen, at times on credit. Outwardly, I couldn't sense any tension or hatred. Our housemaid was non-Jewish. She took care of our cow and took her out to pasture. She also cleaned the house and took care of its maintenance. There was another non-Jewish man, who was like a member of the family, who took care of the cowshed. The local inhabitants, the Horodochucks, who did not work in the fields but worked in forestry, seed trade, manufacturing boots or selling ice cream, considered themselves as of a higher status than that of the villagers. Their wives worked in the gardens, growing vegetables and fruit. They brought the drinking water, which was drawn from the river and carried home in buckets. I cannot recall any violent incidents between Jews and Christians, and it never occurred to me that they are liable to abuse us in the future.

Indeed the Jews of David-Horodok, and of the district in general, have suffered a lot from pogroms that the Christians launched every time there was a change in regime, still, these pogroms were not held by the local Christians but by others who came from outside of our town. In one case, my sister Esther hid herself from the attackers, in the house of our non-Jewish neighbors. I remember that when I was about 3 years old, in one of the pogroms, I hid at night, together with my mother, in a garden near our house and I started crying, and my mother, of blessed memory silenced me.

At home, I heard many stories about pogroms against the Jews. My mother had a little scar over her eye, and she told me that she got it from a blow of a Russian soldier's rifle butt. I also heard that in one of the pogroms, when the Jews could not collect the money for the collective fine that the Russian conqueror imposed on the Jews of the village, the White Russians, under the command of Balachovitz, killed my uncle Israel Hershel, my mother's brother. This happened in the village Ruble, on the holiday of Simchat Torah. When the Polish entered the city of Pinsk, they executed 36 Jews, among them the father of Reuben Liberman, my townsman and a friend of mine (eventually he immigrated to the Land of Israel, formed a family and his two sons are among my friends). This event gained an international resonance.

In the first years that followed the holocaust, I used to wonder, why did they know to tell about the pogroms and persecution, while we didn't speak at all about the holocaust. I really don't know if this is a question of openness. Anyway, I remember that when I heard these stories, I thought to myself: what terrible things happened to the Jews. Later, with all the hardship that I had gone through during the time of the holocaust, these stories that I heard as a child came back to my mind.

As I already mentioned, our town used to be transferred from regime to regime, quite frequently. During the interim periods, when the town was left without any regime, the local Jews and Christians used to cooperate and the local Rabbi of David-Horodok, Rabbi Ravinsky, served as an authority in town. In one case, under the Bolshevik regime, the authorities in Looninyetz sent a group of soldiers to our town, with the task of confiscating herds of cattle from the wealthy Horodchucks landlords, who, naturally, resisted the confiscation. The church and, extraordinarily, the Jewish community in town openly supported the local Christians. In retaliation, the soviet army sent a punishment company and executed three seniors of the town - two Christians and one Jew, Beitzel Yoodovitz, in accordance with the numeric proportion between Jews and Christians that existed in our town.

As I already mentioned, the Jews dwelled in the center of our town, and the Horin River, in which we, children, used to bath, crossed the town outskirts. It was a sandy and quite tidy beach; to reach it, we had to cross a Christian neighborhood. We knew that as we cross this neighborhood, the Christian kids will throw rocks on us, so we never crossed there alone but always in groups, and we used to throw rocks on them in return. But, usually, there was no physical contact between them and us, neither did exist any friendly relations with them. We studied in the Hebrew school and they studied in the Polish school. Our education level was higher than theirs. Quite often, the Christians were satisfied with a small number of years of study, because the families used to utilize their children to help in making a living. On those days, we didn't call it anti-Semitism, but it was obvious that the Christians do not like Jews. Hatred of Jews was always there; I was born into it and accepted it as a fact of life.

In my looks, I resembled my mother. Like her, I was blonde, and although till the age of 14 the school did not allow us to grow hair, because of lice; I still could be taken as a gentile, because of my looks. In Vilna, when I understood the meaning of anti-Semitism, I very well grasped the difference between a gentile and me. But, in our town, with its population of 12,000, all the Jews knew each other, and it was easy to guess who is Jewish and who is not. We could easily differentiate between Jewish and gentile kids. It never occurred to me that I could walk in the street without being identified as a Jew. In this context, during the holocaust, we used to say that the non-Jews cannot identify foreign Jews, but everywhere they can easily identify "their own" Jews. In my days in Europe, after the war, no one could tell that I am Jewish, but in our town I was recognized as a Jew, and the same was during my studies in Vilna. Years later, after the holocaust, on my way to our town, six years after I left it, one of the women in the village of Chorsk, recognized me, made the sign of the cross and said: "Oy, this is Muravchick's son". This was one of the reasons why only very few Jews survived, they looked like Jews and felt like Jews, and what revealed their identity was not necessarily their looks.

After the war, in 1945, when I testified before the Anglo-American committee, which finally recommended that 100 thousand certificates be granted to Jews, they wanted to know why the Jews do not assimilate and stay in Europe. I explained to them indirectly that there was no question of assimilation. Would the Jews want to assimilate, society was closed for them. The state of the Jews in our area differed totally from that of the Jews in Germany. In Germany, Jewish children studied in German schools and therefore there was some assimilation. The same situation was in Warsaw, the Polish capital, and in other large cities in Western Europe. To us there was no assimilation problem, as society did not accept us - not the analphabetic Russians in town and neither the educated students in Vilna. We were born Jews, have been raised and grew up as Jews. Practically, this was a Jewish state, a state within a state.

The Jews' economic state was, relatively, better than that of the Horodchoocks. The real poor people were the Christian villagers. The swamps did not allow developing intensive agriculture. Rye did grow abundantly in the entire area, but white flour, of wheat, should have been brought from the Vohlin area in the South, since wheat did not grow in our area. In general, the entire area was very poor. The Christian villagers did not have real shoes and they used sandals made of tree peelings. Our dresses were also better than theirs. In those days, poverty was mainly expressed by lack of food and poor dressing. We didn't feel inferior, on the contrary, we felt as of a superior status. Without knowing the meaning of a Ghetto, we, willingly. lived in one, as did the Jews for many generations, and wouldn't it be for Hitler, may his name be blotted out, life itself and this way of living would continue till this very day.

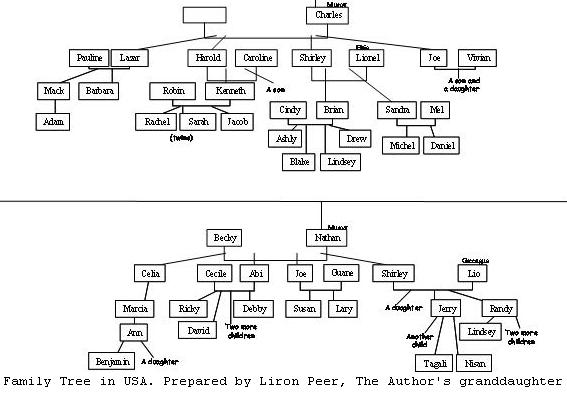

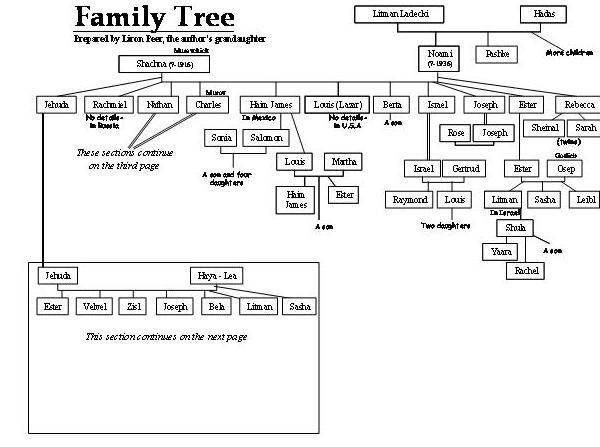

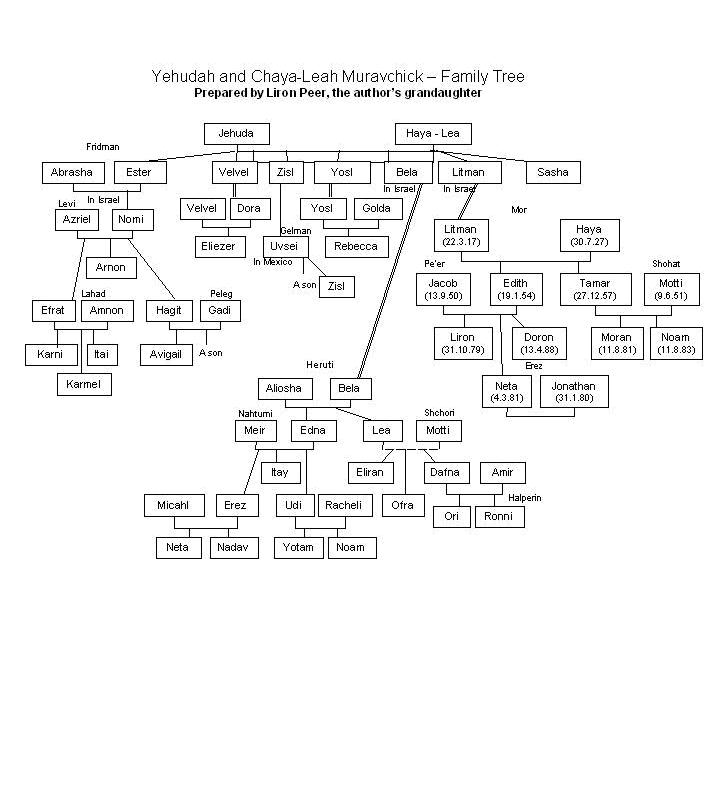

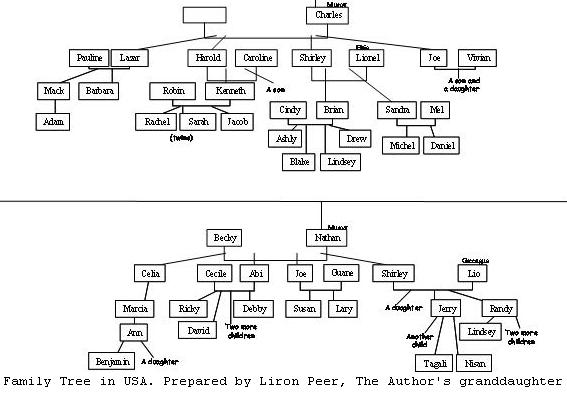

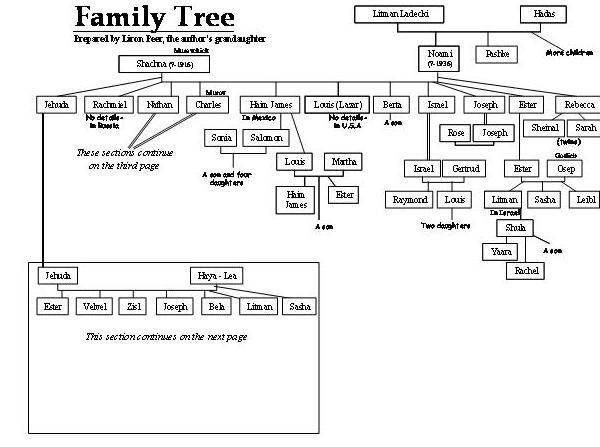

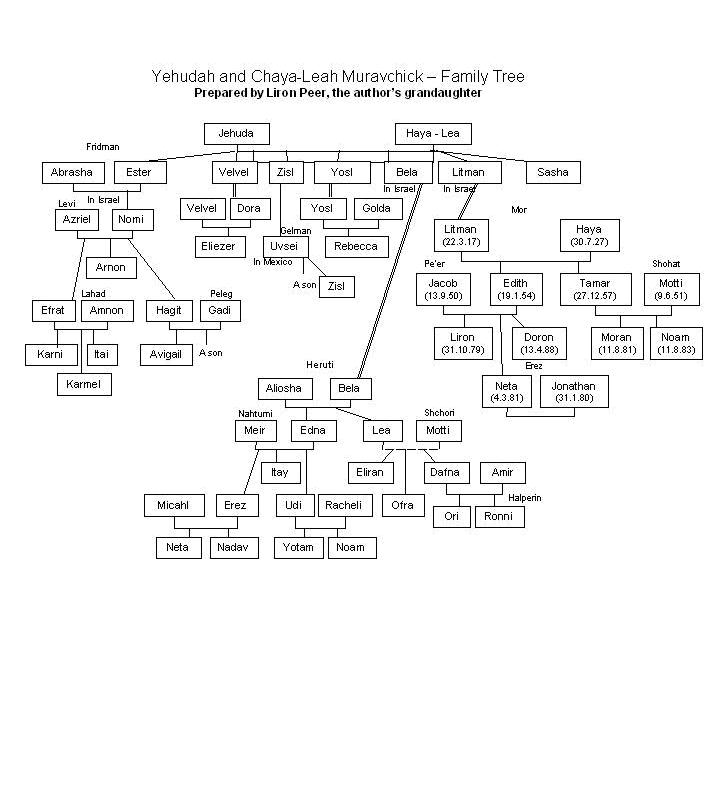

The economic state, even though it was good, was never stable. Worse than that, it was hard and almost impossible for a Jewish young man to find employment and provision. David-Horodok, like entire Pollese, had seen many waves of Jewish immigration, which started in 1905, during the Russia-Japan war, and the October revolution. Among the Jews that immigrated in the United States, on that year, were also my three uncles, my father's brothers: Shlomo, Naftali and Lazar. My aunt, Bashke-Berta, my father's sister, joined them in 1916, and the brothers Yossel and Israel, joined in 1921. The brother Haim immigrated in Mexico in 1924. In the twenties, there was another wave of immigration of Jewish families from the area to the United States, Canada, Cuba, Argentina, and Eretz Isroel. In the thirties, because of the difficult employment situation, there was another wave of Jewish youth immigration to Eretz Isroel.

As World War I ended, in 1918, a very hard inflation started in Russia. In a very short time, the Ruble lost its value until it was totally abolished. In 1921, the Riga agreement was signed. Following this agreement, the new border between Poland and Russia was set. The Polish entered and the border stabilized. Also, before that, the region was transferred from regime to regime, but after the border was hermetically closed, the situation worsened even more.

Since the main transportation was through the rivers, the inhabitants of the region in general, and specifically the Jews, were linked more to Ukraine and Belarus rather than to Poland. As the border closed, they were suddenly cut off of their centers of economy and culture. Following the annexation to Poland and the closing of the border, my two brothers, one of which graduated the Polytechnic in Yekaterinoslav, were forced to become salesmen in my father's linen trade store. During the thirties, the situation of the Jews worsened significantly. The Polish authorities imposed very high taxes on petit commerce, which was mainly in the hands of Jews. Remembered notoriously is the Polish minister of finance, Grabsky, who during his term in government caused many bankruptcies among Jewish businessmen.

At that time, their relatives who immigrated in America assisted financially a great part of David-Horodok Jews. They were also helped by money from the J.D.C. ("Joint"), and from charity organizations. For example, my grandmother, my father's mother, lived on money that her sons sent her from America. It is possible that they also helped my father at this stage or other, but all the members of our household worked in the store. My mother used to go to the market at 4 am, and opened the store, to avoid the possibility that a villager would come this early in the morning and find the store closed. At 6.30 am, after a short Morning Prayer and breakfast, my father would arrive at the store, to replace mother who returned home to prepare lunch. At 8 in the morning, my brother Yossel would arrive at the store, to work on the task for which he was responsible - the accounting of the business. Between 10 and 11, my brother Velevel would arrive to work on the store's public relations and to purchase merchandize from Warsaw and Lodz At noon, father would return home and eat lunch, and then my mother would bring the food to my two brothers who ate in the store. After a short noon rest, father would return to the store, which was open till 8 in the evening. Thus, our store was open 16 hours continually, from 4 am to 8 pm.

At our free hours and holidays, I too would join working it the store. I was assigned to watch that customers shall not steal and that they pay what is due to us. At times, I worked as cashier. I suppose that at a certain time, we were considered a wealthy family. We did not suffer hunger, although the variety of food was very narrow. Meat was quite cheap; the villagers sold potatoes and in the yards at our homes there were, usually, small gardens of vegetables and fruit trees. In our yard, there were 2 cherry trees and two apple trees. My grandmother had a garden with cherry trees and once every year the grandchildren were allowed to pick the cherries. By the seasons, we used to make marmalades of various fruits, strawberry, forest berries, and raspberry. Marmalade made of red raspberry was used as medicine for fever, we used to call it in Yiddish "the marmalade for not to be needed". Still, even though from the financial point of view we were quite well off, at home I learned the value of money.

Father saw to it that all his children would get education, even though the economic situation was difficult. My oldest brother, Velvel, used to travel a distance of 500 km., on a steam ship, for acquiring his matriculation certificate, in a technical-commercial school in Yekaterinoslav (Dnyeperpetrovsk), on the banks of the Dnyeper. My sister, Esther, after graduating public school in our town, continued studying in a secondary school at the district city Mozir. My brother, Yossel and my sister Bella, of blessed memory, studied privately with a Russian teacher.

I was the sixth of seven children. When I reached the age of six years, I started learning with a Melamed (religious school teacher), Shimon Leichtman, in what was called "a revised Cheder", where we learned Hebrew in Hebrew, as opposed to the traditional Cheder in which they learned Hebrew in Yiddish. Of course, on those days there was no such thing as kindergarten. (My teacher's daughter, Zelda, immigrated eventually in Israel and recently I have been in contact with her). When I reached the age of seven, in 1924, the Jewish public school "Tarbus" (culture), in which the studies were in Hebrew, was re-established, and I was accepted into grade Alef.

The teachers were mainly from our area, and later on, graduates of the teachers' seminary in Vilna joined the school team. Heading the school team was the principal Reuven Mishalov (who later became honorary citizens of Haifa). Of the teachers, I wish to mention Yaakov Blumenkopf, a graduate of the Warsaw seminary, who later changed his name to Yaakov Ben Yossef, and was the principal of Tel-Aviv "Daled" city secondary school. Also Abraham Olshansky and his wife Leah Teitelbaum, Yossef Begoon, Haim Baranchook and Palevsky.

The studies at the Tarbus public school ended at 3 pm every day. For provision, we used to bring from home a bread and butter sandwich. I was a very good student and, in the 4th grade, I was granted a "golden certificate" which meant that I got very good marks in all subjects.

We didn't own purchased toys, as is normal today, and we played together various games without needing any special equipment. Like in any group of children, there were some violent kids among us. The education system was secular Hebrew. Indeed, we used to cover our heads when we learned Bible, but as typical in the entire Tarbus school network in Poland, the school orientation was more Zionist than religious. We learned of the suffering and persecution of the Israelites, through the destruction of the first and second temples, the expulsion from Spain, Chmelnitzky pogroms and the revolt of the Maccabbees, the story of Massada and the heroism of Yossef Trumpeldor. In literature lessons, we learned Kiddush Hashem (martyrdom) by Shalom Ash and "In the City of Slaying" by Bialik. The teachers implanted in us the Zionist awareness and, thanks to them, we became aware of the historic continuity of our people throughout the generations. But the teachers' work did not stop at that, in addition, they prepared the students for continuing to study.

Every now and then I wonder, about the teachers in our forsaken town in the midst of the swamps of Pollese, which was cut off from the world, how did they succeed in teaching us and bestow us with knowledge, without modern teaching methods, how did they prepare us for life and managed "to make humans" of us.

In our town, there was also a Polish public school. But, in spite of the fact that the studying there was free, most of the Jews in our town preferred to send their children to the "Tarbus" school, which cost tuition. This is also valid for the very hard economic time that existed following World War I. I believe that Jews in general, and Lithuanian maybe more than other Jews, made the education of their children as their first priority. Indeed, many of our town youth studied in secondary schools outside our town. I point this out, because, in my opinion, this shaped our personality and maybe in this lays the explanation for our obstinacy.

In our town, youth movements of all trends were practically active. The vast majority of them were Zionist. I, as well as all my contemporary friends, belonged to a youth movement. Since I came from a relatively well-off home, I was influenced by the liberal ideology and was a member of the "HaShomer HaLeumi" (The National Guardian), which later became "The Zionist Youth". Other youth movements were: "HaShomer HaTzair" (Young Guardian), "Beitar", "Freiheit" (freedom), "HeChalutz" (The Pioneer) and "HeChalutz HaKlal Tzioni" (All Zionist Pioneer). There was no activity of the Bund movement. During the thirties, the Zionist movement with all its sections was almost the only party in our town. I can remember one youngster who was a Communist. We considered him as one who left the just way. In my youth movement, I became aware, for the first time, of the Dreifus trial, and got an idea about anti-Semitism in Europe and about education, which is oriented and preparatory towards Aliyah to Eretz Isroel. At that time, we used to read a lot, in publications by Omanut Publisihing, about the settlements in Eretz Isroel.

In seventh grade, we published a magazine by the name "HaSneh", in which the classmates wrote articles with a Zionist nature. I was a member of the class magazine editorial stuff. My classmate, Yaakov Kitayin (a member of the Usha Kibbutz), whose handwriting was beautiful and legible, used to write the magazine with Indian ink on a Shapirograph (a white paper sheet coated with gelatine), a technology that no longer exists. I used to duplicate the papers for distribution. The Shapirograph needed to be recoated every now and then, as while being used, it absorbed the blue color of the ink. I used to remove the old gelatine and mix it, while warming, with some new gelatine (for saving expenses) and coat the Shapirograph. Who knows, maybe this activity is the reason for my choosing to become a chemist.

The official language was Polish, but, since the majority of the population in the district were Belarusian who spoke Russian and so did my brothers and sister, who grew up under the Russian regime, had command of the Russian language - the Polish language was not fluent in our mouths. The big city was Lithuanian Brisk, and the language common among Jews was Yiddish in its Lithuanian version (as opposed to Yiddish in Polish version). In my family, too, we spoke Yiddish "Mamme Loshen" (Mother's tongue) and at school, I acquired the Hebrew language.

During the thirties, when Abraham Olshansky was appointed school principal, he promoted Hebrew and tried to make it our everyday language. We all belonged to the "Bnei Yehuda" organization and, within this organization we had sworn to speak Hebrew also at our homes. Indeed, we started to speak Hebrew with our parents and even with the Christians maids. I remember that every now and then, when teachers from outside of our town came to visit us, they were surprised to see that everybody spoke Hebrew, even some of our housemaids.

In 1931, at the age of 14, I graduated the Tarbus School, equipped with a load of knowledge, mainly in Jewish studies, but also in general studies. Practically. I can say, that I owe my life to the school, which educated me, first and foremost to human values and Zionism.

*) As renowned, in Czarist Russia, Jews were allowed to dwell only within Special Settlement Boundaries that were allocated for them, except for very rich Jewish merchants, or those whom we called "Siberinicks", Jews that served in the Czar's army, at least 25 years.

| Previous | Table of Contents | Next |