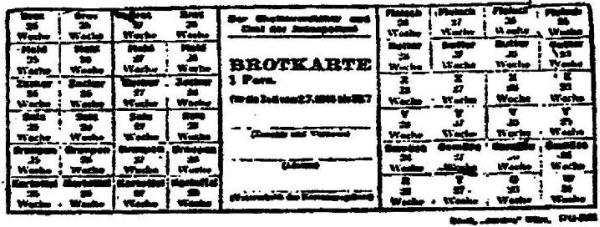

Forged food cards, printed in the Vilna ghetto underground printing press, by Itzhak Kovalsky and Litman Mor.

| Previous | Table of Contents | Next |

The total number of Jewish partisans, on Lithuanian soil, is estimated to be 1,000 men, and their number in the Naroch forests was, relatively, larger than in other places.

From the Vilna ghetto, there were about 150 men, and the rest came from adjacent towns, Vileika, Molduchnoe, Kurinietz, Globky Miadiol, Swienzin. Already in 1942, Jewish families were hiding in the forests and, although the partisans were presenting obstacles in accepting Jews, the younger men among these families joined the combatant lines. The condition for being accepted was having a riffle. They used to say: "kill a German and bring a weapon". Also there were Jews, who fought within the Red Army and managed to survive after the Red Army retreated, these in particular concealed the fact that they were Jewish, or they would be exterminated.

In the Lithuanian brigade, there were Jews that came from the Kovna ghetto, and other Jews that were parachuted from Moscow to head the brigade. As Jews, we tried harder to excel in all assignments and battles. We were strongly motivated, and we did not want to give the accusers any reason to speak against us. Ever since my student period, I knew that from Jews more is expected. What a pity that, with time passing, I forgot the names of the heroes who had fallen in battle.

I remember an incident that occurred in one of the winter days, when Bomka Boyarsky, commander of the reconnaissance company, a Jewish young man from Russia, got killed while galloping on his horse, leading the company. He was one of the Grodno group, who arrived in Vilna and from there went out to the forests.

In the regiment, there were with me another three men and one woman, three of them from the Vilna ghetto, and another from the surrounding area, we were in different squadrons, and there was a medical orderly in each squad. Prior to going on battle, we the Jews, agreed to assist each other, in case of injury.

I won't be exaggerating if I say that the harder assignments were always given to Jews. My regiment commander, for example, used to place me at the most dangerous locations. I remember that I said to myself that I wish that what he wishes me should happen to him. Indeed, in one of the battles, that commander was injured in his leg. But I did not feel satisfaction; on the contrary, I felt bad and my conscience tortured me.

I do not tell this with bitterness. Anyhow, our life was given to us as a gift. But, there is a certain bad remainder left, spitefully of the gentile partisans' conduct at times of rest. They used to tell stories about Jews who evaded fighting. There were endless jokes about "Avram". Avram was a nickname for a Jew, and they used to pronounce it deliberately in ridiculous manner.

Here is one example of a joke that is engraved in my mind. Ivan and Avram enter the recruiting station. The recruiting officer asks Ivan: "are you healthy?", Ivan responds: "Yes, I am strong as two". To everybody's astonishment, Avram turns to the door to leave the room. The officer asks him: "Avram, where are you going?" and Avram responds: "Ivan just said that he is as two".

I remember a partisan, from Kiev, who told that the Jews kidnapped a Christian boy in Kiev, for performing a Jewish traditional ritual (probably, the famous Beilis Trial). I was shocked to hear from a Russian partisan, who was born already after the revolution, in a big city, in the heart of Russia, that it is better that the Jews go to Eretz Isroel. Of course, they always added: "Here is, we don't mean you. You are, spitefully, a good Jew".

In our company, there was a "Politruk" (political commander), in parallel with the company commander. The company commander was a Ukrainian, who graduated a technical school. We had a correct and even well relationship. He did not emphasize hatred for Jews. He probably appreciated me not exactly as a combatant, but as an educated man. This relationship did not stop him from imposing on me assignments, above and beyond.

The Politruk was a Soviet Jew. He did not reveal this fact, not even to us, Jews. He posed as Russian in all aspects. The partisans did not like the Politruks, to say the least, and here they had yet another argument for it - why does he conceal his being Jewish. Of course, this argument was turned to me. This way, I had to suffer twice - once for being Jewish myself, and a second time for the Politruk being Jewish.

The Communist party had an important status in the forests, but it was not like in Russia. During the war, there was a kind of liberalization, at least in the foreign direction. Stalin, in his famous speech, praised the Russian people's effort and its contribution to the war. He embraced religion, altered the national anthem and the military uniform, and more.

Often I wondered what is the source for the hatred and on what is anti-Semitism based. This question is accompanying me ever since, as of the time when I studied in the university, and I didn't find the answer yet.

In the ghetto, the Germans called us "dirty Jew", and among the partisans I heard that they say about me: "he is bathing like a Jew", meaning that I am bathing too much. I always had soap, and in our company, it was known that they could get soap from me. When we used to go out for supplies, while they were looking for vodka, I searched for soap.

With the partisans, we used to eat from one bowl, which was placed in the center of the table. When I returned from a watch task, when they all have finished their meal, I would eat alone and bring the bowl closer to me. I overheard someone saying: "he eats like a Jew".

I met Russians who never saw a Jew in their life, and while chatting with me, they did not believe that I am a Jew. There were partisans who schemed against the Jewish families that hid in the trenches in the forests. We had to beware them when we, Jewish partisans, attempted to bring some food to these families. One should not generalize, but only a few, very few, sympathized and helped Jews. Practically, a good gentile was considered one who did not scheme against Jews. I assume that there must have been those who helped Jews, like Yassik, of blessed memory, who was ready to take an enormous risk and give me shelter in his house, for no reward. I personally did not encounter many Yassiks.

It is no wonder that many Jews concealed their being Jewish. I, personally, met a Jewish female physician, whom I knew from my time in the Vilna University. One winter night, I was on watch outside. Temperature fell to minus 25 Celsius. A strong wind was blowing and my gums froze, the pain was unbearable. She treated me, and when I noticed that she is concealing her being Jewish and her past, I too kept silent.

At the beginning of the conquest, my wife's family found shelter in the village, with gentiles, for money. When the situation worsened and the gentiles could not keep them any longer, they, together with other families from the area, found hiding in the forest. My wife (whom I didn't know yet) told me, that one day she suffered from an eye infection, and one of the partisans took her for treatment to the brigade doctor, Dr. Perevosky, a Jew from Vilna who posed to be Polish. As they entered his room, he throw her out of the room and threatened to hand her over to the brigade headquarters, claiming that she wasn't at all allowed to enter the brigade boundary, which was off limits to ordinary civilians.

I had no problems in my regiment. I, more or less, integrated well and became 'one of the guys'. Nevertheless, all complains and critics they had against the Jews were addressed straight to my face.

I learned to drink Samogon (homemade vodka). In one of my visits with a peasant in Laddy, where my regiment was stationed, that peasant told me: Stay with us after liberation, I have a daughter at her prime.

At that time, Markov, our brigade commander, added to his staff the poet Suzkover, the painter Bogen and the poet Kacherginsky (who, after the war, got killed in an air accident, in south America), in order to document the brigade history. At this occasion, one of my comrades approached me and asked: "how come that all the Jews are historians?" The argument against the Jews was that they evade fighting and, usually, prefer easy administrative tasks (Jobniks). My high education stood in my way, more than once. "I know what you will be after liberation", told me one of them, "you will be an accountant". And the word "accountant" he pronounced in a mocking manner.

Under such circumstances, I very often missed the time when we were with the Bogen group, only Jews. This I felt in spite of the combat conditions that were much harder. The attitude towards Jews, not specifically to me, left an unpleasant residue with me. Since my childhood, I was a Zionist with a national consciousness, and the students' hatred, during my study at the university, as well as my time with the partisans, strengthened this unpleasant feeling. I did not want to tie my future with the USSR. And in the fifties and even later, when anti-Semitism in the USSR became enormous, I wasn't at all surprised.

When we arrived in the forest, from the Vilna ghetto, we wanted to fight as Jews. I already told about the denial of our request to be organized in a Jewish regiment. In the fifties, they would consider such an organization as treason and crime against the regime. The elimination of Jewish authors, the Doctors' Trial, Stalin's plan to expel all Jews to Siberia, the accusations against Zionism and the anti-Israeli policy, all originate from the Communist attitude towards the idea of national self determination in general, and, particularly national determination of the Jews.

I fought together with them, shoulder to shoulder, but I was like in an inner ghetto, I knew that our way would be separated. As one who did not live in the USSR, was not a Soviet citizen, and did not belong to the Communist party, at any stage, not even in the forests, I could not say proudly, like my comrades - "we are fighting for our homeland".

Still, where did we derive the power to fight and to overcome all physical and mental difficulties? I, who had undergone the humiliation of the "Benches Ghetto" at the university, the Vilna ghetto, the German atrocities, the feeling of being a stranger among the partisans - fought, first of all, for defending my own personal dignity. I felt that I am not just a Soviet combatant, but I am also, mainly, a Jewish combatant. I felt that I fight for the honor of the people; the people to which I belong since birth and along the years, willingly, thanks to the Jewish education that I got at my home as a child. I felt motivated by the sense of belonging to the Jewish people, to which I was forcefully pushed, as an adult, by the hostile environment, without opposition on my part.

I admit, the chapter of anti-Semitism in the forests, I mention with a heavy heart. After all, we fought together against a common enemy; we ate of the same plate, suffered together, and survived together. I don't feel a sense of discrimination, but I would be doing wrong to the historic truth if I wouldn't relate to this subject. Moreover, this part of my story explains the decisions I have taken after the war, which affected my entire life.

In retrospect, I am trying to understand, if not to justify, the Soviet policy during the war. They, and not only they, but also the allies, made all the efforts not to give the war the character of the Jews' war against Hitler. In my opinion, this was exactly the reason that the allies did not bomb Auschwitz and other concentration camps, and not military obstacles.

Nazi propaganda did everything to persuade the world that Jewish international capitalism and Communism, for which Jews were the cornerstones, enforced the war on Germany. Still, the allies could drop from the air leaflets to warn all collaborators in Europe, that, after the war, they will be held personally responsible for murdering Jews.

Only those who were there can understand what an encouragement this would have been for the Jews, who were doomed for being murdered, or those who needed superhuman powers to continue fighting and surviving.

I remember that on one night in 1943, Soviet reconnaissance plains flew above Vilna in the Prussia direction, we wanted, actually prayed, that they would bomb our ghetto. It was then that I grasped the meaning of the phrase "let me die with the Philistines".

Forged food cards, printed in the Vilna ghetto underground

printing press, by Itzhak Kovalsky and Litman Mor.

| Previous | Table of Contents | Next |