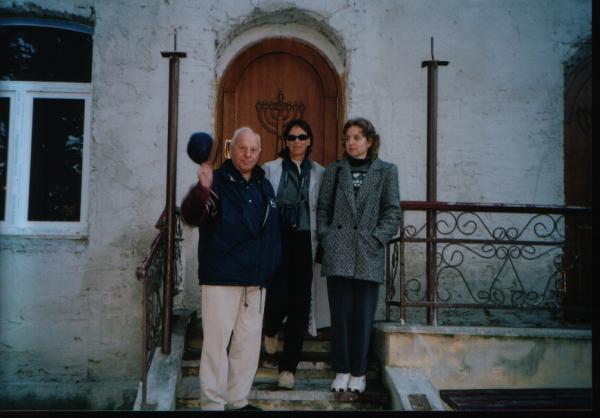

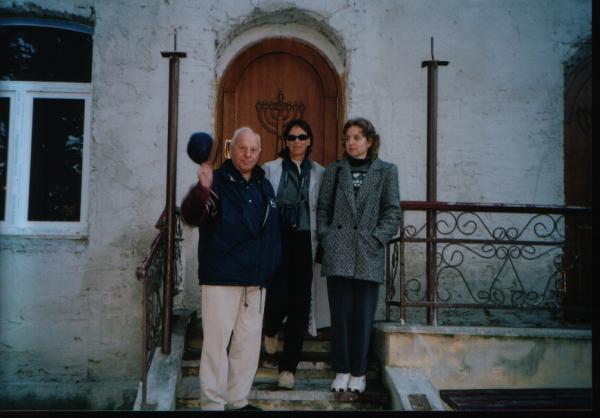

The only synagogue left in Pinsk 2003

| Previous | Table of Contents | Next |

Because of Volodia's leg shooting incident, Shura was arrested and taken to Markov's headquarters. Markov knew Shura from the days when they were both teachers in a Swienzin school, during the Soviet era.

He released Shura and instructed him to organize a group of Jewish combatants. The group consisted of 20 members, and it was given a status of a "Spez Group" - a special company. We were ordered to gather intelligence information at the surrounding area, and to provide food to our comrades in the labor group that constructed a small airfield, near the village Looz, not far from base headquarters. And if we manage to get weapons, we will be allowed to join the partisan fighting regiments.

The airfield was designated as base for parachuting weapons and for Red Army small aircraft traffic, for communications. At night, we used to light fires and the aircraft would parachute light weapons.

The supply of food to our comrades, who worked in constructing the airfield near Lodz, was difficult. The brigade headquarters had allocated a specific area, and only in that area were we allowed to get food "donations", according to the rules set by the partisan movement.

In areas under partisan control, it was forbidden to make people "donate" or take from them anything. It was only allowed to eat in such places. The area that was allocated for us was quite distant, and during the day it was under German control, therefore we had to enter the villages only at night, which was very risky.

On one night, as we returned with seven carts loaded with food, we encountered a German and Lithuanian police ambush, that opened on us heavy fire. Luckily, they fired tracer bullets, which are very dangerous at direct hit. By watching the direction of these tracer bullets, we succeeded in escaping them, leaving behind us the carts loaded with food and with clothing for our comrades, who construct the airfield. Miraculously, we suffered no casualties. At morning, we arrived in a farm that belonged to a Polish noble, and was deserted by him as the Soviets arrived. Gypsies, who escaped the Germans, occupied it now.

Shura and I entered the house, and one of the gypsy women offered us potato pancakes. Apparently, we should have felt good, since we didn't have to expect any danger from the gypsies, as they, too, were eliminated by the Germans. But, for some reason, I felt inconvenient. I left the house and settled on a haystack. This gave me time to think of my unconscious fear of gypsies; seemingly, this is something that stayed with me since my childhood. I thought that hatred of the Jews is the result of the gentiles' not knowing the Jews. Many among them, never saw a Jew, and their fear and suspicion of Jews is similar to my subconscious fear of gypsies. I met Russian partisans who never saw a Jew in their life, and who had negative prejudices about Jews.

In the group, there were people of Lintop, Swienzin and Kurinietz, who knew the area well and who had contacts with the people in it. In the group, there were also Ralla, Shura's wife, Shimon Zimerman and his wife Rebecca, the brothers Musia and Selim Shnitzer and myself.

We had very few riffles. Bogen had a Czech riffle, Zimerman had a Russian riffle, the Shnitzer brothers shared one riffle, and they never separated from it. When we went out for operations, their condition was that they should go out together to every assignment. I had my "famous" riffle with only two bullets, but seemingly, it had a deterrence impact. Once, when we went out on an assignment in one of the adjacent small villages, one of the Lintop's men fired my riffle by mistake. This left me with only 50% of my ammunition.

We were together as a group for about a month and a half. The assignments were dangerous, mainly because of the lack of weapons. Nearby Swienzin, four of our men were killed in a surveillance task. But, when I compare this period with other periods, I am filled with pride for the manner in which we fulfilled the assignments that we were given. We were an integrated group, brothers in arms. The term "combatants' brotherhood" was an everyday reality for us. Till today, when I meet with friends who were in the group, I tremble, my heart warms up, and I remember the good times we had together. The bad times, and there were many, have been pushed away into a forgotten corner.

In November 1943, the group was dismantled. Some of us have been transferred to the main headquarters base; among them were Shura and his wife. Others were transferred to the labor regiment and others to the fighting regiments.

At that time, weapons were parachuted and the brigade mobilized combatants from the villages in the area. At last, I got a new Russian riffle and was assigned to the Suvorov regiment. About one month later, a new regiment, "Povieda", which means "victory", has been set up, and I was assigned to that regiment.

Most of the time I have been with the "Povieda" regiment, which consisted mainly of Ukrainians who cooperated with the Germans, and joined the partisans after the Stalingrad defeat. There were also Russian war prisoners, who escaped from prisons and hiding places. The Russians encouraged those who cooperated with the Germans to join the partisans, and the account they settled with them after the war.

The gathering of partisans in Naroch started in 1942. In one of the operations, the partisans succeeded in eliminating the Miadiol police station that was stationed in a school. Once a junction had been taken, the area of partisan operations had broadened, at first only at nights, and later in daylight too.

We mobilized local boys. Our regiment numbered 100 men, among them four Jews - one of them a woman. I was the only Jew in my company and there was a Jewish Politruk, who impersonated as Russian.

In the area in which we were active, there was also activity by Polish underground men who belonged to "AKA" (Armja Krajowa), who fought the Germans, but also fought the Russian partisans. They should be blamed for the death of many Jews who found refuge in villages or forests.

The catholic population usually sympathized the Poles, and the Orthodox population sympathized the Russians. As the relations between the USSR and the Polish government in exile in London got worse, the Russian partisans' headquarters exterminated all Polish officers in our area. Our regiment took part in the battle with the Polish partisans and we succeeded in pushing them off across the Villia River, to the west bank, which was populated by catholics. The partisan combat tactic was to avoid a direct, face-to-face, encounter with the enemy. Our regiment was assigned to protecting the area which was under partisan control, not only at night but also in daylight, a kind of garrison force, to blow up railroads, to attack and eliminate police stations in villages and in small towns and, mainly, to ambush German transportation and logistic axes on main and secondary roads.

In face-to-face combat, we always suffered losses, because of the German superiority in manpower and in arms. We exerted to attack, hit, and retreat to the forest as quickly as possible.

I had experienced two blockades, and we were ordered to disperse into small groups, not to enter any combat and to infiltrate through enemy lines. More than once we sat in ambush and the Germans didn't arrive, because they, too, had intelligence. But, practically, our goal was achieved - transportation and supplies at night hours were completely halted.

Knowing to speak Russian, Polish, German and a little Lithuanian, I tried to learn to what side the population is inclined. When I attempted to make a peasant talk about his inclination, especially while I took from him food or clothing, which was legitimate by partisan rules, the typical answer used to be "I give everything to your riffle, not to you", that was a sort of insurance policy for every bearer of arms.

The area we were in was always in dispute between Russia and Poland. My interest in peoples' inclination resulted not only from curiosity; it also had to do with security. The national affiliation was according to religious affiliation. The Orthodox considered themselves as Belarusian, while the catholic, who were with a strong national consciousness, had a strong Polish inclination. The Belarusian usually cooperated with the Russian partisans, while the catholic cooperated with the Polish.

The peasants never resisted giving food. Partisan rules prevailed in the area. The Germans did not enter the forest during the nights, and even in daylight, they preferred to avoid it. According to partisan rules, we could go in, take food, and get out; it was forbidden for us to equip ourselves with a stock of food. The areas under German control were divided into sectors, and every regiment was allocated a sector in which it may take food. The fact is that the peasants were really in a very bad situation. During the day, the Germans with their Lithuanian collaborators would come, and at night, the Russian and Polish partisans would come.

Staying in the forest, during the summer season, was reasonable, but in other seasons, we had to find shelter from the rain and, in the winter, also from the snow. The partisans and the noncombatant Jewish families, who found hiding in the forests, dwelled in trenches. A trench was not meant to be like a bunker that is capable to resisting German weapons. We constructed the trenches of coniferous trees, without nails. The walls were assembled of boles placed on one another with dirt between them; the roof was made of boles densely covered with crisscross coniferous tree branches, which prevented rain and snow from entering. Our beds, too, were made of boles on which we spread a layer of branches and leaves. In the winter, we would make a fire near the front entrance to the trench.

We slept on the boles in our clothing. I permitted myself to take off my boots, and it happened several times that when a shooting started at night, I had to get up and run with the boots in my hands.

In a trench, about 15 partisans "settled down".

In 2003, I traveled with my two daughters on a "routes" trip and insisted on entering deep into the forest to where our regiment was stationed. The guide led us on marked paths that where known to him, and we reached the trench of Markov, our brigade commander.

In the winter of 1944, the partisans controlled a wide area. Our regiment settled in the village Laddi. In every house in the village, 4-5 men settled. When we had no special assignments, we acted as a garrison force. But, most of the time, we were assigned to operations. All day long, we held military training and at nights, we went out for operations.

We were occupied with setting ambushes for German supply convoys in the surrounding of Vileika, Postav and Molduchno.

Years later, when I was on a business trip to Denmark, I took a tour on a ferry from Copenhagen to Malmo. On the ferry, I met a German who was disabled since World War II. We spent a day together and this gave me a chance to hear, first hand, about what the partisans did to the Germans. This German served in the German Transport Corps, in the area where I acted as partisan. I asked him, without revealing that I am one of the partisans that where there, and he told me about that time, from the German point of view. Signs of fear of that time could still be noticed on him. Indeed, the partisans caused severe damage to the German logistic regiments.

Contrary to what is normally thought, the rule in partisan regiments was very tough. We were at the enemy's rear and the discipline was very strong, including the clearly defined hierarchy between commanders and soldiers. Commanders dined separately from the soldiers, they picked for themselves the pig's inner parts that were considered better, and the soldiers got its meat.

We had no military uniforms. Our clothing we took from the villagers, but the hierarchy was maintained, like in the army. Day and night, 24 hours daily, we guarded the base, to prevent infiltration.

Losing a weapon was cause for court martial with a mortal risk threatening the offender. My partisan friend, Moshe Shootan, fell asleep while being on guard and faced court martial. We had a saying: "if you fall a sleep on guard, you fall asleep forever".

One night, when I was on guard, I was very tired and seemingly sleepy. My section commander who performed an inspection approached me and I didn't manage to ask him for the password. He threatened me with severe punishment and called me a traitor, but, luckily, of this, too, I came out in one piece.

Our military assignments were focused on eliminating the local police in the small towns of the forests area. This way we acquired control over many villages, to an extent that the Germans did not dare to visit them, not even in daylight. Our regiments constituted the garrison that guarded the area against a sudden attack.

The soviets dropped parachutists that were equipped with automatic weapons, and constituted special groups that were active in sabotage and in intelligence.

The main activity was linked with the disruption of German supply axes, especially trains that carried military equipment and supplies to the Soviet front.

At nights, we would go out, in small groups, to blow up railroads along a few kilometers. Along the railroads, there were German bunkers with machineguns. These night operations, quite often resulted in heavy casualties. Indeed our regiment was hit by deadly fire and suffered many dead. I successfully survived the physical burden, I suffered from lack of sleep, but it was very hard for me to bear the ugly treatment from our Ukrainian comrades. Every time we returned from an operation, often after suffering severe losses, they used to grumble because nothing happened to the Jews.

In 1944, the night train traffic was almost completely halted. We used to place charges beneath the rails, usually where the rails curve. On those days, there were no remote control devices, so the operator lay to the side of the railroad, and as the train approached, he would pull the rope and the charges exploded, causing the train to fall off track. To prevent this, the Germans used to place before the train, a few carts filled with sand, so that in case of explosion the carts that carried the military equipment would not be damaged.

To make it impossible for the charges operators to hide, the Germans cut down all the trees on both sides of the railroad, at a width of about 50 meters on each side. The partisans were forced to change their method, and began to apply the "railroad war".

Each one of us got four explosive charges and in one night, we had to blow up four rail tracks, a track in each direction. In one case, after we blew up the railroad, we sought hiding in the forest, near the railroad, and on the next morning, at 10 o'clock, a German train passed on that railroad. It seems that the Germans mobilized forced laborers in the area, and succeeded in repairing the railroad.

Nevertheless, the partisans caused a lot of damage to the Nazi army and to the German supply transportation. As time went by, the partisans took control on more and more wider areas along the east front, from Ukraine in south to Belarus in the north.

In the winter of 1943/44, the Soviets freed Stalingrad and the Germans suffered a severe defeat. In the spring, the Red Army advanced also in the Vitebsk front, a few hundred kilometers from our location.

In retaliation to the heavy damages that the partisans caused the Germans, the Germans set up the second blockade, in the spring of 1944. They gathered large forces, and attacked the area in two fronts. On the west side of the Molduchno-Vileika railroad line eastwards, and from the front westwards. Again, we found ourselves surrounded.

The Germans entered the villages with large forces and destroyed property and equipment. They, practically, emptied the villages and many of the men, local residents, were deported to Germany for forced labor. It is hard to describe the difficult situation in which the villagers, most of them elderly people, women and children, found themselves.

In this blockade, the Germans succeeded in pushing off the partisans in the front direction, and left the east side of the railroad almost clean of partisans.

Our brigade positioned itself west of the railroad. Our regiment has been assigned to cross the railroad to the eastern area, which was supposedly clean of partisans, attack the Germans from there and sabotage their logistic roads.

For a few weeks, night-by-night, we ambushed and attacked German supply convoys. Not like at the western side of the railroad, the eastern side was sparse with forests and the danger was great. There was almost no food, since, as mentioned, the Germans emptied the villages, and we were forced to settle with potatoes that we found in the fields.

I will describe two battles that I remember well: One, not far from Kurinietz. We sat in ambush, near the road, at some distance from the town, and waited for a German convoy that was expected to arrive from Vileika in the Kurinietz direction. Our regiment commander sent me to an advanced position in the Vileika direction, about 200 meters ahead of the regiment positions. I was to return and notify the commander when the German forces will be revealed.

Suddenly, I heard shooting, spitefully from the other side, the road to Kurinietz. Probably, the Germans found out about our plan and, in order to expose our regiment, instead of sending a convoy to Kurinietz, they sent from Kurinietz a squad of policemen, Belarusian collaborators. The regiment began firing at the policemen and, after causing losses to them, withdrew back into the forest.

The day had dawned, and I couldn't find the regiment, that was already in the forest. The feeling of being detached from the regiment was even harder than the battle itself. A partisan detached from his regiment was in a bad situation. My situation as a Jew was even sevenfold worse. A gentile partisan could find shelter in some village, but for a Jew there was no chance for survival

The very fact that our regiment had been exposed, almost in daylight, was a bad sign. On the following day, we attempted to cross the railroad and join the brigade at the railroad west side. But, an armored train spotted us, started shelling us, and we were forced to withdraw. Since it was impossible for us to advance in daylight and since there were no dense forests in the area, we settled, during the day, in a few houses in the village. At twilight, Germans and local policemen, who came from Dolhinov, suddenly attacked us. I was cleaning my riffle when the attack started. A firefight had developed and, before we managed to move on to the forest, seven of our comrades were injured. This was at the end of May, the night was short, and we had to move with the wounded to the railroad and cross it with them before dawn. We improvised stretchers of boles and belts and carried the wounded on our shoulders. I still remember the physical effort of carrying an improvised stretcher, especially the pain that the boles caused to our shoulders. However, more than the pain, I have engraved in my memory the feeling of deprivation. The Ukrainians, my comrades in arms, took turns in carrying the stretchers, while I was forced to do it continuously. No one turned to me, to replace me, and I said nothing, because, anyway, the Ukrainians used to grumble towards me: "none of the Jews was injured in battle". The fact is that, at that time, we were only two Jews in the regiment.

It is an irony of fate. One of the wounded, that I carried that night on my shoulders, was a local young man from one of the villages, whom we mobilized to the partisans. Before the operation, he approached me and complained: "It is all because of you. It is you that the Germans are looking for".

At that moment, I tried to put myself in his place. I thought that from his point of view maybe it is logic. After all, he could have stayed peacefully in his home, since the Germans were after the Jews only.

As we attempted to return to the forest, during the fire battle, I stayed close to my squad commander, whose fighting experience was better than mine, but, mainly, the reason for this was that I did not want him to have anything critical to say on my conduct in battle.

When we reached the forest edges, he ordered to stop shooting, since the Germans were shooting at us with machineguns. There was a deadly fire, bullets hit the trees and leafs and whistled near our ears. We were only a few meters from the forest. I remember saying to myself that this is the end, then I remembered one of the songs that we used to sing - about a partisan who had fallen in battle and no one knows where his grave is. (By the way, in Hebrew, this song is called Be'Arvot Ha'Negev (in the Negev prairies), the lyrics were translated from Russian and adopted to the original Russian melody.It was very popular during Israel's War of Independence).

At that time fragment, I remembered my sisters in Eretz Isroel, and a thought crossed my mind that somebody has to survive and tell what we went through. I took courage and advanced into the forest. At night, the shooting stopped, and we advanced with the wounded towards the railroad.

On the way, we crossed a river and got wet to our bones, none of us made a big thing of this. Before morning, we arrived at the railroad and had to cross the rampart. Here, a German armored train, that regularly passed every morning, to clear mines, that we used to lay at night, spotted us and opened a hell fire on us. We were ordered to cross the rampart running, with the wounded on our backs. Running, we got away from the train, with the bullets whistling over our heads.

Miraculously, we were saved and arrived wet and deadly exhausted, to the village in the area, which was considered partisan area. Immediately after our arrival, we had to start guarding our force, and I was the first who was ordered to go out and stay on guard.

The only synagogue left in Pinsk 2003

| Previous | Table of Contents | Next |