| Previous | Table of Contents | Next |

On September 6, 1941, the Germans started to expel the Jews from their homes to the ghetto boundaries. The evacuation went on systematically: the Germans entered a Jewish neighborhood and, street after street, took down the Jews from their apartments, and led them, in rows, to the ghetto.

On that day, my friend and I went, as usual, to our work at the railroad station. On our way, we saw in the adjacent streets Jews being led with their belongings, as much as they could carry in their arms and on their backs. As I mentioned earlier, we lived in a district that was mostly Polish, and in our district, there was no special commotion on that morning. As we arrived at the railroad station, we realized that our Jewish friends did not come to work. We felt very uncomfortable.

My friend and I did not want to stay out of the camp. Anyway, a thought of escaping didn't occur to us, first because there was nowhere to escape to. Only very few, outstanding people, were ready to endanger themselves in hiding Jews. The thought that guided me on those days of uncertainty and mortal risk was that what happens with everybody will happen with me too.

Now we were facing a new problem. How to return home to pick up some cloths and necessities and join the others, without risking being kidnapped. We arrived at our neighborhood, with no problem, but when we were close to our home, two Lithuanian policemen, who wanted to take us to the prison, stopped us. I responded in my broken Lithuanian and told them that we are on our way to the ghetto, and they let us go. The "system" worked again this time. Or, maybe, down to it, it is all a matter of luck!

We quickly went up to our apartment, packed a few cloths and things, took along some food, as much as we could carry, and joined a group of Jews that were marching in the street. Together with all the rest, we walked towards the ghetto.

Odd as it may seem, I remember that I felt relieved, almost elated. It was very difficult to live in the mixed district were we lived. It was dangerous to walk in the street, and I thought to myself, at last we will be among Jews. Not that I hated the gentiles, but living among them was impossible. Again, the sense of belonging to the society, the community, the people, escorted me as of the "Tarbus" school, not to mention father's home. I thought that among Jews we'll be safer, and the saying "sorrow shared by many is a half comfort" has acquired a tangible meaning.

We walked silently and introspectively to the ghetto. Each of us thinking of his fears and worries. I remember the scene: gentiles standing on both sides of the street, I did not expect and indeed did not see any sorrow or sympathy in their eyes, and this, of course, is to say the least. Suddenly I noticed one of the students whom I knew from the university. I did not lower my eyes, on the contrary, I stood up and raised my head, and I refused to seem humiliated in his eyes. On his sleeve, he wore a ribbon with a swastika on it. I remembered the "Benches ghetto" in the university. For me, the ghetto started then, when I lived in a country that pretended to be democratic and in which I was supposed to live as a citizen with equal rights. The trauma there was more painful, maybe not physically but surely mentally.

The yellow patch was not only a sign for identification; it was also a symbol, like all the other Nazi laws. You had to walk in the middle of the street like a horse or cattle, it wasn't allowed for Jews to travel in public transportation, you were constantly exposed to scheming, and, on the other hand, you could have been kidnapped with mortal danger that is stronger than all the restrictions.

Out of the mass murders, of which we didn't know yet, everything else was done according to the law. The Germans set the rules and announced them publicly, there were no secrets, and the world was not alarmed to help. The minute I was obliged by law to wear the yellow patch, I had no choice but to wear it, as I am naturally a law abiding person, even though I resent it.

In Vilna, there were two ghettos - the big one and the small one. Both ghettos included the narrow streets of the old Jewish neighborhoods, whose inhabitants were evacuated to Ponar on the "provocation" night. The synagogues area was in the small ghetto. On September 6, 1941, 40,000 of Vilna Jews were moved into these ghettos.

When we arrived in the ghetto, we were housed in the empty apartments. We were forced to crowd about 100 persons in every apartment. Together with me, in my room, there were about 30 people more, women, men, children, and old people, among them also the Alperovitz family. The crowding was horrible.

At night, we would lay very densely on the floor. Turning from side to side we did together, as one person, as if by order. It is hard to describe the unbearable density. Naturally, this aroused conflicts between the people. Like, the fight on the stove. In Vilna kitchens, there was a large brick stove, on which there were three cooking spots. Old newspapers heated the stove. I have no words to describe the mothers' worry for their children, and the power of the instinct for survival. Endless quarrels, regarding the use of the large cooking spot, were carried on between mothers. Of course, I don't blame them. Indeed, it is hard to describe the situations to which a human might arrive at times of hunger, when he is fighting for the lives of his children.

While on the way to the ghetto I felt a kind of elation, during my first days in the ghetto I was in severe distress. I was alone, without family, I had no one to worry for, and I observed everything like from the outside. Under such circumstances, my concern had strengthened; I wondered, all the time, about what is going on at home, how do my father, mother, and family manage. And, in the ghetto, I watched the people and wondered why, at such a time of trouble, there is no cooperation, only quarrels, arguments, and screaming. It was obvious that it is impossible to live like that. The sense of helplessness and suffocation oppressed me more and more.

I felt that I must get out of the ghetto. Rumors started about actions that took place in certain streets of the ghetto. I started to look for work (work, again!), outside of the ghetto.

On September 15, the Germans took another 3,000 Jews from the ghetto to Ponar. Luckily, with the help of the employment bureau that had been established in the ghetto, I found work as chemist for a Koenigsberg German company, that dealt with disinfections of barracks, to prepare them for the entry of the German army. A group of women has been adjoined to me. They sealed the windows with paper and glue and I burned a solution of Sulphur dioxide, which evaporated, filled the rooms, and killed the bugs. On the next day, I would go in, ventilate the rooms and proceed to another location.

The work wasn't hard. I favorably remember our German foreman, who was an elder man, an invalid of World War I, who demanded nothing from us except a job well done. And this we gave him. On Yom Kippur, he responded to my request and released our group from work on that day. More than once he defended us from the scheming of young Germans, at about the age of 18, probably of the "Hitler Jugend" groups, who threatened us with weapons and with shouting "Run! With us you run and don't walk!".

At the end of Yom Kippur, on October 1, 1941, there was another action. The Germans took another 5,000 people from the ghetto to Ponar. Till this day it is not clear to me how did I survive. This is how it happened: The Jewish police announced that all holders of "schein" (work certificate) should report at the gate of the ghetto. I didn't know about this. But, at that time, in any case, I wouldn't volunteer to any special assignments, as it was too dangerous. When the quota of 5,000 people didn't fill up, the Jewish policemen, with the Germans, went from house to house and took out the men until the quota was filled. They simply didn't get to our house. There is no logic explanation to this. The interesting point is that every time that we weren't caught, we rejoiced as if we were rescued forever.

I believe that there is a fate for each person. This was the feeling that had been with me all the time, and it became even stronger when I joined the partisans. Although I wasn't raised in a religious home, but only a traditional one, I believed then and still believe in a superior power, the possibility that there exists a guiding hand. That doesn't mean that a man should be a fatalist, as in the proverb "god helps those that help themselves".

Then came the "night of yellow Scheins". The Germans, through the work places, issued "Scheins" to all those who were employed in vital work. Each Schein had the name of the employee on it. Yellow Scheins, 3,000 of them, were distributed to those who were employed in vital work. All those who held a yellow Schein could get from the Judenrat three more Scheins, in pink color, for their spouse and two children. My work place was not considered vital. Priority was given to locksmiths and other professionals who were employed in military units.

A short while after the distribution of the Scheins, on the night of October 24, the Germans locked the ghetto, no going out or coming in. At the same time, the Germans issued an announcement that holders of yellow Scheins must report at the police to get the pink Scheins for their family members, and at the following day, a selection will be held and all holders of yellow and pink Scheins will be transferred to the small ghetto, which was empty. At that time we already knew more about what is going on, a short period earlier I joined the underground. It was clear to me that they intend to take to Ponar for extermination, all those who will remain, and I may be one of them. I knew that I must act. I was very upset and in great hunger. I ate all the food that I possessed. I shaved and dressed properly, hoping that if I looked good and qualified for work, the chances for my survival will be better.

Through the whole night, I ran around, along the ghetto borders to find a breach in the fence, through which I will be able to escape. But the ghetto was tightly sealed and I couldn't find an escape. I was trapped.

Quite often, and more during the first years after the holocaust, I dream of that terrible war, I never dream of hunger. But, again and again, this nightmare returns to me, the desperate search for a breach in one of the ghetto walls, to save me from the bitter fate that awaits me.

I did not lose my senses. I searched for some way out, and I didn't know yet what it is going to be. I turned to the ghetto police station and watched the line of "happy ones". Here my eyes caught the Buch family, who were distant relatives from Vilna. The father, a doctor, of course got a yellow Schein, as an employee of the ghetto hospital, so did the daughter, who was a nurse in the hospital; she had her own yellow Schein. The solution seemed obvious. If I introduce myself as her husband, I will be entitled to a pink Schein and my life will be saved.

And so we did. I joined the line and, with their agreement, of course, I introduced myself as Mr. Buch, the husband of Mrs. Buch, and I was given a pink Schein. My friend Alperovitz did as I did, and so we were rescued again.

I always believed and still believe that it is forbidden to give up. As long as there is a fragment of hope, there is also a chance. This is also true with medical problems. The one who fights for his health has more chances of recovery than the one who is desperate and is giving up. During the entire war, and more so after I joined the partisans, I used to say to myself, consistently, that I should keep my head up high, out of the water, that despair does not contribute to survival. The fact that I survived was not on others' expense. Many held yellow Scheins and did not get others to join them.

On the following day, we went out, in a small caravan, to the small ghetto. During the day, the Germans emptied the large ghetto and in the evening, we were returned to, seemingly, a secure shelter, the large ghetto. At the end of October, the Germans exterminated the small ghetto and murdered about 2,500 more Jews.

Alperovitz, my friend's father, has been kidnapped by the Lithuanians, at about a month earlier, while he was on his way to work, under circumstances that were never clarified. His mother managed to get out of the ghetto and found, for money, shelter with a Polish family in one of the villages adjacent to Vilna. This time, my friend was rescued, together with me, but at about a month after the action, he joined his mother and they hid there till the liberation. Our contact person was the Polish maid Yadzia, who was loyal to the family and helped me too, every now and then, by bringing to me, at my work place, food and cloths that I left in the apartment. I sold these in the ghetto to a pawnshop. A Lithuanian policeman, who during the Soviet period, used to be a Soviet policeman, robbed the major part of my belongings from the apartment.

My friend Iziya Alperovitz had a Jewish appearance and this aroused a problem of getting him out of the ghetto and taking him out of town, to the Polish family. Alperovitz also owned a sawmill in which a Polish guard, by the name Yassik worked. On the day of my friend's escape, my friend Alperovitz and I, with my Aryan look, and my friend Farber from Olkiniki, had escorted my friend, while mingling within a group of workers that left the ghetto. At a certain phase, we separated ourselves from the group and I transferred my friend to Yassik, about whom I will later elaborate. (Yassik rescued Farber and his wife. They immigrated in Eretz Isroel and later he served as Rabbi in a synagogue in Tel Aviv. His son is also a Rabbi - second generation to holocaust survivors, an Israeli native, he is among the management of The Association of Jews from Vilna and vicinity in Israel(.

Following the yellow Schein action, there was some relaxation in the ghetto. Under the direction of the Judenrat, the ghetto inhabitants managed to run a seemingly normal life. The Judenrat organized the various communal institutions. There were schools, synagogues, Yeshivas, an employment bureau, a housing department that collected rent and distributed food cards, a hospital, and - of course - a police, not only one but three: a police for criminal affairs, economic affairs and sanitation affairs. There was also a theatre and a choir. Life went on as if in an autonomous administration. People began to think in terms of hope. Here, the ghetto is productive and the Jews are useful and contribute to the war effort, therefore there are good chances that the ghetto will hold on and that we will survive.

We lived our everyday lives; no one made calculations for the longer range. At that time, I began to work in the Judenrat housing department. My job was to allocate living space, which, according to the Nazi instructions, was 2 square meters per person, so that in one room there were 3 to 4 families. Density was unbearable and quarrels and screaming went up to the sky. In those days, everything had significance. There was a difference between a living space near a wall, or window, or door. A space in the corner of a room was considered a thousand times better than one in a passage area. I wonder many times how did I, relatively young, succeed in straightening disagreements between families, older people, with regards to things that to me seemed of no importance.

My position was different. On one hand, I suffered from loneliness and from concern for my family. I was responsible only for myself, I had no one to worry for, and I, myself, was content with frugality. Sometimes I would cook for myself; at times, I would even cook a Cholent (traditional meat stew) with some horsemeat that was rationed by the supply department. Bread was also rationed and food was reduced, of course, we also starved. Still, I do not carry memories of hunger; I probably had other worries that were more serious. I supported myself by selling cloths that I transferred from the city into the ghetto. I also applied my experience in disinfection work, I used to do for the Germans. The walls of the apartments in the ghetto were covered with wallpaper full with bedbugs. I burned bricks of sulphur basis; the sulphur dioxide would evaporate and kill the bugs and insects. Still I had a lot of time for "introspection". Already in the university, I personally experienced ant-Semitism; I never integrated in Polish society. When traveling from Vilna home, on vacation, a distance of 350 kilometers, the road passed by many "Pale" settlements - small towns. I used to watch the Jews who got on the train, at the various stations. All spoke Yiddish, segregated from the gentiles in the way they dressed and in their entire way of living. Polish society and culture were totally alien to them. Sometimes, a thought crossed my mind, that maybe the Jews' unwillingness to integrate in their environment is one of the reasons for anti-Semitism. I thought that maybe the Jewish society is too secluded. And here came reality and slapped our faces.

I did not accept this reality. At times, I would go out of the ghetto with a group of workers. On the way, I would take off the yellow patch and go for visiting Yassik, the Polish contact person, who helped in hiding the Alperovitz family. Sometimes I would sleep over at their place and I used to retrieve a lot of encouragement from this. Such a conduct and such a readiness to take risks were very rare. We were all aware of the danger to which those who had relations with Jews, even minor relations, were exposed. It was truly a mortal risk. Obviously, I too put myself in danger. In spite of my Aryan looks, it was dangerous to walk out of the ghetto in a town where I may be recognized.

One time, as I walked out of the ghetto, while walking on the sidewalk without my yellow patch, I was seen by a Polish acquaintance of mine. I am not sure that he had recognized me. Luckily, I got out of this unhurt. My Polish friends never told me about what is going on in Ponar, in spite of the fact that they must have known that a mass murder is going on there. I am not using the term genocide, here, because at that time we weren't convinced that practically there is a planned and systematic murder going on. We thought that this happens only in Lithuania, because of the Lithuanians who retaliated for the Soviet period. Only after a few years, we learned that, in January 1942, the Vanse Conference had decided of the final solution, the extermination of the Jewish people everywhere, not only in Eastern Europe. Indeed, as of that January, the Germans started systematically to dilute the ghetto.

During the relatively calm period, that prevailed in the ghetto, at the end of 1941, youth began to get organized. These youngsters, most of who arrived in Vilna, in 1939, from all over conquered Poland, waited in Vilna to immigrate in Eretz Isroel, via independent Lithuania. These groups consisted of young people with no family. Only a few of them succeeded in immigrating in Eretz Isroel, the majority got stuck in Vilna, like me.

On May 1940, Zionist activity has been completely banned. To the extent that it continued, it had to go down underground. Therefore, even before the Germans entered Vilna, there already existed in the city a nucleus of Jewish underground. In the ghetto, we started to renew the social relations that we had in Vilna, on the basis of "the trouble of many is half a comfort". Naturally, everyone turned to the youth movement to which he belonged before. There was cooperation between the various youth movements, within the framework of "the coordination", a sort of coordinating committee of all the Zionist youth movements.

I belonged to the "Zionist Youth" ("Hanoar HaZioni") movement, which was linked with the General Zionists party in Poland, headed by Yitzhak Greenbaum. My connection with the movement has renewed through Nissan Reznik who was active in the movement even before the war, and in the ghetto became one of its leaders.

The connection was on a social and mutual help basis. Of course, in the ghetto any organization was illegal. The "Zionist Youth" ("Hanoar HaZioni") people, with me among them, used to meet in the kitchen at Strashoona Street No. 2. This was a sort of soup kitchen, managed by Yehudith, Reznik's wife, and at noon, in addition to the poor food we got rationed with the food cards, we got a little soup. Very quickly, this soup kitchen turned into a center for gatherings and meetings of the "Zionist Youth" ("Hanoar HaZioni") people. Naturally, we discussed current issues, what is going on in Ponar? are Jews really being murdered there or maybe they are sent to labor or concentration camps?.

All sorts of rumors spread in the ghetto. One rumor was about a woman who returned from Ponar. According to the rumor, the woman was captured by the Germans in one of the actions and was taken the Ponar forests. A bullet hit her, but it only injured her and didn't kill her. After the murderers left, this woman got out of the pit and found her way back into the ghetto. But, since her story seemed odd, there were those who said that she is crazy and suffers from hallucination.

On the other hand, there were rumors about letters that are coming from concentration camps, from people who were kidnapped by the Lithuanians, and it seemed that they were taken to labor camps and were not murdered. We didn't know what is true and what is false. Probably the Germans, who wanted to conceal their operations, spread the rumors about the letters.

Man is optimistic by nature; he is destined to life not to death. Man always wants to believe that there is hope. You see - there was no precedent in history of the mass murder of a peaceful population. Man's survival instinct is so strong that it suppresses any possibility that opposes the natural instinct - the will to live.

Still, a serious doubt began to nibble within us. And even though there were those who believed that in Ponar a murder of Jews is going on, we were sure that this happens only in Lithuania and not in all the occupied territories.

One day, the Coordination sent to Warsaw one of the "Zionist Youth" ("Hanoar HaZioni") activist, Solomon Entin, a refugee from Pinsk, who escaped from the Russian zone to Vilna, with the intention of going to Eretz Isroel. The purpose of his being sent to Warsaw was to transfer information to the youth movements regarding the occurrences in Vilna and Lithuania. We already knew that there is a ghetto in Warsaw and that all the decrees that are imposed on us are imposed on the Jews in the Warsaw ghetto as well. But, we did not hear of systematic murder, which we feared that is going on in Lithuania. On his second trip from Vilna to Warsaw, the Germans, in Malkinia, near Bialistok, caught Solomon, and we never saw him again.

On the assumption that this is happening only in Lithuania, a part of the youth movements, especially the "HeChalutz" movement, got organized to transferring people westwards to Bialistok, a distance of about 200 kilometers from Vilna, in the Warsaw direction.

In December 1941, we began to be convinced that the killings in Ponar are according to a systematic plan, which was set up by the Germans and is executed by the Lithuanians. The Lithuanians cooperated with the Germans due to their hatred of the Jews and their belief that the Germans will recognize a free Lithuania. They formed special squadrons "Ippatinga" who executed the mass murder in Lithuania and Belarus.

Sylvester night, December 31, 1941, is well engraved in my memory. On that night, after we filled the hall with rows of benches, all the youngsters gathered in the kitchen at Strashoonah Street 2. I remember myself standing on a bench near the wall. The kitchen was crowded fully. We were a group of about 150 people; boys and girls, who shared the same fate. Abba Kovner, of "HaShomer HaTzair", stood there and read to us the famous manifest - "let's not go like lambs to the slaughter".

It is important to understand that, from our point of view, this was the secondary message of the manifest. We, who were present at that time in that kitchen, heard for the first time, loud and clear, what we whispered to each other and to ourselves: "Ponar is death".

Indeed, earlier I already reached the conclusion that the Germans are executing a mass murder. But I based this conclusion on whispered rumors. It was hard to believe that such a terrible thing is happening just a few kilometers from us. But when Abba Kovner read his manifest in front of the members of the movement, the words were well absorbed: "Ponar is death", "Ponar is death". Once the words were heard time and time again, they turned into a truth: "Ponar is death". Only as a secondary grade item did we also absorb the message: "let's not go like lambs to the slaughter".

There is a difference between what a man feels in his subconscious and what he understands and knows consciously. It took some time until we absorbed the truth "Ponar is death". It is a fact that many times, we told each other that in Ponar, masses of Jews are being murdered, but we were not convinced. Every now and then, your partner to the conversation would say: "indeed Ponar is death" and we still refused to believe. Until that Sylvester night in which from the podium Abba Kovner repeatedly said: "Ponar is death".

I elaborate on this in length, because the realization that "Ponar is death" ripened in our minds very slowly, it was a long process. But, on that evening, what was in our subconscious became a conscious fact. And, from that moment on, the conclusion was clear: "we will not go like lambs to the slaughter".

In retrospective, we can say that on that night, the Vilna ghetto Jewish underground was established. It called upon the Jews to rise and defend themselves, not only passively, but also with weapons, if and when they will come to eliminate the ghetto. The name that has been given to the underground was "Fareinigte Partisaner Organizatzie" (United Partisans Organization) F.P.O. To this organization belonged members of the Zionist youth movements in the ghetto: HaShomer HaTzair, Zionist Youth, HeChalutz, Beitar, also the Bund, and the Communist party.

Each youth movement had representatives in the underground headquarters. The representative of the "Zionist Youth" was Nissan Reznik, with whom I had tight connections during all that period. The head of the underground was Itzik (Itzhak) Vitenberg, the representative of the Communist party. With him were Itzhak Glazman of Beitar and Abba Kovner of "HaShomer HaTzair".

I was lonesome, in an isolated society, 350 kilometers far away from my beloved family that remained in Belarus. In those days' terms, it is like the distance between the earth and the moon. No contact was possible. At nights, I dreamt of my family, and neither the dreams carried any hope with them. I was not optimistic with regards to my family's fate. A logical analysis of the situation led to the conclusion that also in David-Horodok the same terrible things are happening. Quite often, I used to remember what my father said, on the day that the war broke out: "from this war we'll all come out equal". This was a sort of a prophecy of fury.

I was sorry for not being with my family and for being unable to help my parents in their struggle for survival. My conscience tormented me. I tortured myself for leaving the house and blamed myself of selfishness.

I was among the first to join the underground. I was not responsible for anyone and it was much easier for me to decide to join. I endangered only myself. I remember the appreciation I felt towards those who had families and joined the underground, in spite of the fact that it endangered their families. From this aspect, joining the underground was irresponsible towards the family members.

Fierce internal arguments were held, on those days, between the underground members: "defense" or "rescue". With "rescue" meaning the search for hiding places in the Aryan side, or moving to the Bialistok ghetto, and "defense" meaning resistance. We, F.P.O members, adopted the resistance idea. The success of the rescue operation was in doubt. In any case, it was only a partial solution, just for few people. It should be remembered that, at the beginning of 1942, partisan concentrations did not yet exist in the forests that surrounded Vilna.

In the beginning of 1942, the relatively relaxation continued in the ghetto. Nevertheless, more and more people reached the conclusion that this is only a temporary situation. There were those who searched for ways to hide among the gentiles, others tried to move elsewhere, if the situation outside Lithuania seemed better.

I could also find a hiding with Yassik, in the city, but I felt tied up with the oath of allegiance to the F.P.O and breaking this oath itnever occurred to me. In my eyes, escaping from fighting meant treason.

In 1956, when I was in the United States, for advanced studies, my wife's parents, who lived in the US, suggested that we, too, move there and settle close to them. Leaving Israel seemed to me like escaping from fighting in the ghetto.

Yassik suggested that I escape from the ghetto and hide in his home. He did not ask for any reward. Yes, there were also such cases, with brave people who rescued Jews, because of friendship or prior acquaintance, and there were even those who hid in their home Jews who were strangers to them, only because they believed that it is their duty to rescue humans because they are humans. In fact, of those that found hiding for payment, many did not survive. In many cases, the gentiles would take the money and then kill the Jews, or hand them over to the Germans.

I don't want to say that this was a war of martyrdom (Kiddush Hashem). I knew Sahlom Ash's work "Kiddush Hashem" and "In the City of Killing" and "Baruch of Magenza", we knew that in Spain, Jews died as martyrs. Of course, we did not want to die, we were young, lively and loved life. We convinced ourselves while convincing others, and indeed, we were convinced. After all, basically, man was created to live and be active in society. At that time, we were united with the everyday material worry to survive and with the concern for our fate, when the Germans will decide to eliminate the ghetto. Our motto was "we will not go as lambs to the slaughter".

The idea of resisting the Germans ripened in me quite a long time. More than once have I seen the rows of Jews being taken to Ponar. A miserable scene that is hard to describe. I preferred dying in the ghetto while fighting, to the unnatural death in the pits of Ponar. Maybe there is some selfishness in this, but, I, being alone, could afford "this pleasure" for myself.

No one dreamt that there is a slight possibility of wining this war. The German army surrounded the ghetto, in the midst of a hostile environment. Strategically, this was a lost game. F.P.O members never had any military experience. Accidentally, I had undergone some training with weapons, during my studies in the secondary school, but most of us, including the leaders, had no military experience. Only a few of us knew what army is.

Because of the circumstances and the dangers, the underground consisted of a few hundred members. All the activity was done under strict compartmentalization (conspiracy) conditions. Each underground member had contacts with a group of only five members. Heading our group of five was Chaim Lazar, of "Beitar", and when he left for the forests, in 1943, I became the leader of this group. In our group, there was also Senya Rindzunksy, who later immigrated in Israel and wrote here the book "The Destruction of Vilna", which was published by Ghetto Warriors Kibbutz and The United Kibbutz.

Our contact person with headquarters was Sonya Madeisker, an intelligent and brave woman, who was also active after the extermination of the ghetto, within the Communist party, until she was caught and executed by the Gestapo. After the war, a street in Vilna was named after

her.

We trained with arms, mainly pistols that were stolen, acquired, or smuggled into the ghetto. We also had three machineguns; of course, it was impossible to use them. My training summarized in getting to know the pistol, I learned how to properly disassemble and assemble it.

As I already mentioned, after the "Yellow Scheins Night", I started to work at the Judenrat housing department. It sounds terrible; the Judenrat is identified with serving the Nazis. But, this had significant importance, since this job made it possible for me to know all weapon hiding places. My superiors in the department, was Glazman, the head of Beitar in Lithuania, and one of the leaders of the ghetto underground, and Chvoinik, of the "Bund" movement, one of the founders of the underground. I lived in a room with my friend Alexander Ridzunsky, and our room served as the underground printing house.

Itzhak Kovlasky of Beitar, was the printer. His experience in printing he earned before the war, and I, the chemist, contributed my knowledge for composing printing colors and in the printing work. The printing letters set-up, we had stolen in the city (see Itzhak Kovlasky's book in English, about the underground printing press).

At nights, we would take out all the accessories from our room, and go to the Strashon library, where we printed various announcements and a daily news bulletin that contained world news. Underground members distributed the bulletin and announcements, only to underground members.

I will not forget my excitement when we heard, from the Polish radio in London, about the Jews' rebellion in the Warsaw ghetto. In fact, the Vilna underground had planted the rebellion seeds in Warsaw. The messengers from Vilna ghetto forwarded the information about the events in the Vilna ghetto and, following this information that reached Warsaw, the underground started to prepare the rebellion.

In the printing press, we also printed forged food cards. These cards were transferred to the underground headquarters, the food that was obtained has been sold in the market, and the money was used for the purchase of the weapons.

Within my work at the housing department, I had to distribute the food cards to the ghetto residents and to collect the rent. Those who held a Schein were entitled to a food card, and I have been strict that a person who is not entitled should not receive a food card. There were people who disappeared or escaped and left their Scheins in the ghetto. At day, I was observing the law, and at night, I broke it for the sake of the underground. I didn't feel that this is wrong. Breaking the law under these circumstances seemed natural to me. The underground, by definition, was against the law; not only the Germans but also the Judenrat didn't acknowledge it.

It can be said with certainty that there was no consensus with regards to the underground, the purpose of which was to resist the Nazis, and its very existence endangered the ghetto. Most Jews in the ghetto saw in the underground a threat on their seemingly peaceful life in the ghetto. They didn't particularly favor the underground. In the next room to mine, in the apartment where I lived, lived a family that came from Kovna. We were in good terms. One day they discovered that in my room there are printing accessories, also, they undoubtedly noticed my absence at nights, of which they concluded that I am involved in illegal activities. They found it hard to believe that a quiet person like me would be involved in underground matters.

Elder people declined to join the underground. Not necessarily because of ideological objection, but, mainly, because of their responsibility to their families. But we wanted to believe that the underground is the pioneer leading the public, and when the day of rebellion will arrive, all the ghetto dwellers will join the struggle.

Towards the end of the year, news infiltrated that in other places, around Vilna, partisans are gathering, mainly in the forests northeast to the city, at the river Naroch area. We faced two options - either staying in the ghetto and fight, or going out to the forests and join the partisans. The F.P.O. official stand was to resist within the ghetto. I supported the underground position, which meant fighting the Nazis till death, without a slight chance for surviving alive. I will risk saying that the Massada idea wasn't alien to us. We were brought up on it in the Zionist youth movements, we knew that the terms "Kiddush Hashem" (sanctification of the Holy Name), and "going to be burned", are like a characteristic sign along the history of the Jewish people. The dramatic change in this attitude happened to me after the " Vitenberg Day", on which I will elaborate later on.

The Judenrat was headed by Yaakov Gens, and his deputy was David Desler. There can be no comparison between these two. We saw in Desler a Gestapo agent, who cared only for himself and for those close to him. Gens considered himself as one who was sent by the public. In his past, he was an officer in the Lithuanian army and his wife was a Lithuanian Christian. It is possible that he could save his own skin, but he considered his task as a mission. He believed that if the ghetto will be productive, the chances for our survival would be better. Most ghetto inhabitants believed his good intentions.

Gens was ready to provide Germany with the quotas that the Germans had demanded, he distinguished between productive youngsters and elder people, etc. He also executed selections and helped the Germans in eliminating the Oshmiena ghetto on October 23, 1942, by sending a squadron of Jewish policemen, who helped gathering the Jews and handing them over to the Germans. They were told that they are being transferred to the Kovna ghetto, and when the train stopped at Ponar, many of them, mostly youngsters from the town Svenzian, tried to escape. The Germans fired on the escapees and only a few of them returned later to the Vilna ghetto.

One day, Gens called for a meeting in the ghetto and tried to explain and justify his deeds. He argued that, thanks to the selections he executed, he succeeded in reducing the quota that the Germans demanded and, thus, saved youngsters instead of elder people.

Both, Gens and Desler, knew that there is an underground in the ghetto and started laying obstacles in its way. Desler principally opposed the underground, while Gens thought that its activities are endangering the very existence of the ghetto, which was productive and contributed to the war effort.

Quite often Gens would say that he himself is willing to rebel and stand up against the Germans, but he should set the proper time for this, when there will be a tangible danger and the Germans will eliminate the ghetto. To his bad fortune, the Germans too knew this, and on September 14, 1943, a few days before the elimination of the ghetto, the Germans shot Gens at the Gestapo yard, as a suspect of assisting and forwarding information to the underground.

Anyway, as a first step against the underground, Gens decided to deport Glazman the deputy of Vitenberg, head of the F.P.O headquarters, to a labor camp near Vilna. The underground headquarters considered this step as a threat and first move towards its elimination.

On June 26, 1943, by order of headquarters, a group of underground members succeeded in releasing Glazman from the custody of the Judenrat police. This event has been entitled by everybody as "The Glazman Affair".

This underground operation echoed strongly, as it was the first time that the underground executed a resistance operation, though not against the Germans but against the establishment that acted while following German instructions. On one hand, it aggrandized the underground's image while, on the other hand, it exposed it, and Gens, head of the Judenrat, gained more power and strengthened his status among them.

Following the Glazman Affair, the Judenrat leaders decided to fire all underground members that were employed in important key positions, and so I was fired from my job at the housing department.

After my being fired, I found a job as manager of a laundry, outside the ghetto. To this laundry German army uniforms, were brought from the front. The Soviet army stopped the German offensive and, from the front, arrived army uniforms saturated with blood that congealed on the coats.

My work was not too hard. On normal days, one's head can spin while seeing blood, but the blood on German uniforms encouraged me. These bloody uniforms were live evidence of the turn that is taking place in the front, a good sign for the future. But, redemption delayed - the front is one thing and the extermination of Jews is a different thing.

I felt neither revenge nor pity; I think that, at that time, all my feelings were dull. Did I wish to see blood? - Yes. The blood on the uniforms seemed to me as the light at the edge of a dark tunnel. Here, the invincible Germans, their end will come. The question was whether we would live to see it.

My situation, at that time, was not terrible. As I already pointed out, physical suffering didn't bother me too much. The survival instinct overcame everything.

I was then 25, a bachelor, without family and responsibility. Indeed, the uncertainty with regards to what is going on at home did not let me rest, but I was not responsible for any one, except myself. Many, at my age, have already been married. I, for some reason, decided that until I meet anyone of my family, I wouldn't form a family of my own. Maybe what my brother told me, when I left home, echoed in my mind: "If I wasn't married and responsible for a family, I would have left town".

I have seen with my own eyes, in the ghetto, families that were exterminated because of family ties. Mothers followed their children; men followed their families. Families refused to be parted and went together, as a whole, to death. Family ties among Jews are very strong, and the Germans knew how to exploit it.

A man judges an event by the outcome, and, since I stayed alive and run a satisfactory life nowadays, I don't regret for acting as I acted. Was this a result of an analytical review? I think not. Although I consider myself a rationalist, it seems that my emotions took over and made me act in the way that I acted.

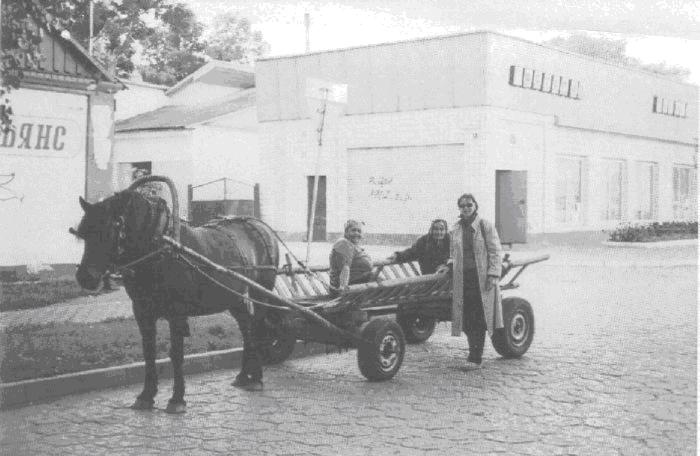

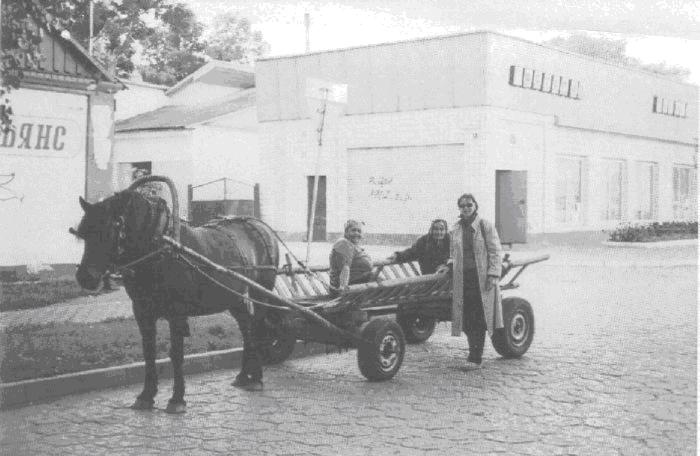

The center of David-Horodok. Photographed at our visit

in 2003. Standing is Dr. Edith Peer, author's daughter.

| Previous | Table of Contents | Next |