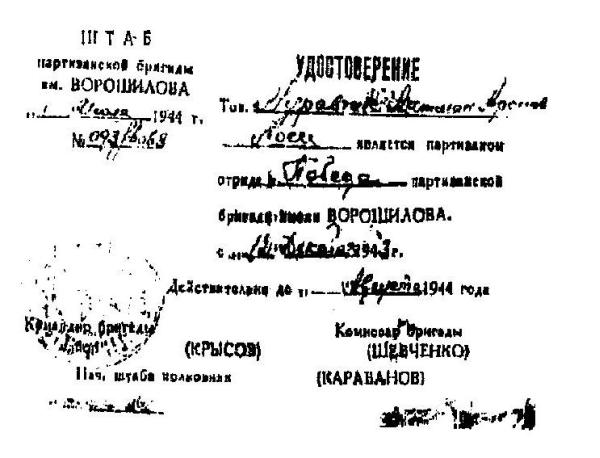

Certificate from the Voroshilov Brigade headquarters, of July 21, 1944, Testifying that Muravchick Litman had fought as partisan within the "To Victory" regiment

| Previous | Table of Contents | Next |

Itzik (Itzhak) Vitenberg, who was the head of the underground headquarters, was at the same time, active within the Vilna Communist party. In July, the Germans arrested another, non-Jewish, activist of the Vilna Communist party and, in his interrogation; he gave them Vitenberg's name.

As a result, the Germans set an ultimatum to the ghetto administration to handover Vitenberg to them, or else the entire ghetto residents will be executed. The F.P.O considered this as a sigh for eliminating the ghetto and the underground, and called for a mobilization of all its members. I was given a pistol and was ordered to wait at an observation point, on the second floor of a building at the corner of the streets Yatkova and Rudnizka, and when I will see that Vitenberg is taken out of the ghetto, I should fire at the policemen that escort him.

I stood at this point from morning to evening, of course, I wouldn't hesitate to follow the order and shoot even at Jewish policemen. After a day of tension, without knowing what is going on in the ghetto itself, I learned that Vitenberg, in agreement with the underground headquarters, had given himself up to the Gestapo.

Later on, we heard that his wife, who survived, blamed the headquarters for applying pressure on Vitenberg to give himself up to the Germans. My friend, Nissan Reznik, who was a member of the headquarters, denies this. In 1989, when I visited Vilna, within a mission of the USSR partisans' organization, I stayed overnight with the Shmuelke Kaplinsky family. His wife Chyenna Borowsky was an active Communist in the ghetto, and close to the F.P.O headquarters. I tried to get her to speak about this, but couldn't learn a thing from her.

It wasn't a simple decision at all. The F.P.O believed in resisting the Germans, on the assumption that at the critical hour, all ghetto Jews will join the struggle. But, the Judenrat leaders, with Gens on top, succeeded in convincing the ghetto Jews, on that day, that there are two options: either they handover Vitenberg to the Gestapo, or they bring the ghetto to extermination. Gens and Desler provoked the ghetto Jews against the underground and presented the case as irresponsible that leads to the elimination of the ghetto.

The headquarters was under enormous pressure. It is hard to know whether the Germans would indeed eliminate the ghetto if Vitenberg weren't handed over to the Gestapo. The "final solution" was known, but the schedule for the various actions was set by the headquarters in Berlin, and was not a local initiative. Most likely, a war between brothers would break out. The underground possessed weapons and the Jewish police had no weapons.

Most of the pressure came from those strong men who worked in the German military units and whose status was relatively far better than the others'. I, personally, and obviously other members of the underground, experienced severe disappointment. The idea of rebellion, which we nurtured about a year and a half, shattered like a soap bubble. The hope that when the time comes, the underground will lead the armed struggle against the German enemy, and all the Jews will join, evaporated as if it never existed

I tied myself with the F.P.O by an oath of allegiance, and escaping from the ghetto to a shelter would seem to me as treason, as desertion from a battle. And here comes "Vitenberg Day" and shuffled the cards. I did not believe that we would be able to involve the ghetto Jews in rebellion even though the elimination will be real, and every hour in the ghetto seemed unnecessary to me.

The F.P.O headquarters, which was seemingly aware of the way the members felt, reached the conclusion that fighting the Germans, within the ghetto, is impossible.

Sixty-one years have passed since then. Vitenberg Day has been deeply engraved in my heart and memory. We must also remember that the decision has been in the hands of relatively young people, in their twenties, without political, public or military experience. I describe the facts as they happened. Is it possible to issue a verdict from such a distance of time?

While I write these lines, our country is in the midst of a difficult dilemma: Should we evacuate the Kattif Block and the north of the West Bank. Again, like on the Vitenberg Day, it looks like as if we are heading towards civil war, between brothers.

Prime minister, Itzhak Rabin's assassination got me into a real trauma. How does a Jew kill another Jew, and a prime minister? I remembered Vitenberg Day and I felt a need to write a few words in the mourners' book, regarding this tragic event. Beyond my sympathy with the family's grieve, I felt a need to mention Vitenberg Day and to warn against a war between brothers.

In his book "The Destruction of Vilna", Alexander Ridjunsky tells that in 1945, when the famous author Illya Ehrenburg visited Vilna after the war, he said that Vitenberg Day is material for a drama, and, indeed, the Israeli dramatist Yehoshua Sobol wrote two plays about those days in the Vilna ghetto.

In spite of the great disappointment that I experienced on Vitenberg Day, for the time being, I survived.

During the second half of 1943 and the beginning of 1944, agitation aroused in Lithuanian ghettos; the number of escape attempts has increased and the lines of the underground were broadened. Information began to arrive from Markov who was the commander of a brigade that acted northeast of Vilna, about 200 kilometers from the city. This information encouraged ghetto youngsters to go out to the forests. Markov, a Belarusian Christian, who was married to a Jewess, was before the war a teacher and Communist. He fled to Russia in 1941, and was parachuted back, by the Russians, to organize the partisan movement in the Naroch forests.

On July 24, 1943, a group headed by Glazman, left the ghetto in the direction of Naroch forests. The group numbered 21 men to whom 14 more joined in Novo-Vileika. On its way, the group encountered a Nazi ambush and many of its men were killed and injured. Glazman managed to reach Naroch with less than 20 people.

The Germans pinpointed the families of those who were killed, and sent anyone that was close to them, to Ponar.

The route to the forest was dangerous. But my mind was set to get out of the ghetto and fight among the partisans. It was an inner urge, and I can't say where did this urge come from. Was it the instinct for survival?, the will to take revenge? I can only say this - when I held a conversation with Yassik, my Polish friend, and asked him what to do, he answered simply "I can't give you advice, and I am willing to help, go hide in my place". He was a simple, uneducated man, a night watch in a sawmill. I often thought that a man's greatness is not linked with his education. He was a man.

Unfortunately, when the Germans retreated from Vilna, after the Red Army entered, on July 13, 1943, Yassik got shot at the fire exchange. His house was at the bank of the Villia River and the river was the front. I learned about this from my friend Farber, who hid with Yassik during the last year of the war. Yassik hid Farber and his wife for no reward, only out of love for men.

On September 1, 1943, the ghetto was put under siege. The Germans and the Estonians surrounded it, and in four days they took out about 4,000 men and women, this time not to Ponar, but to labor camps in Estonia. For filling the quota of Jews, that were to be sent to Estonia, the Germans were helped by the Judenrat police.

At that time, the underground was mobilized again. The few weapons were distributed to the members. I got a riffle and my post was in Strashoona Street, in the Strashon library. Illiya (Yechiel) Scheinbaum got killed in the front post, after launching a grenade on the approaching Germans. The Germans bombed the house and broke contact. We waited in vain in our post, which was only three houses away from the house that they bombed, but nothing happened. The Germans left the ghetto. After these four days, the ghetto started to rehabilitate.

Since the Germans were not interested in a confrontation, similar to the Warsaw ghetto uprising, they saw to it that the Jews that were transferred to Estonia should send letters to the ghetto, to delude the ghetto inhabitants that Estonia is not death, but labor.

My urge for getting out of the ghetto to the unknown was quite similar to the urge that, in 1939, made me leave home for Vilna, to the unknown. I am not a fast decision maker; the matter bothered me a long time until the decision ripened to leave the ghetto, as soon as possible.

By the way, both this events happened on the 11th day of the month. If there are certain good days for a man, during the years, the 11th became a good day for me. In hard times, a man is inclined to adopt various beliefs; probably I also was like that.

Many faced difficult dilemmas, there were those who did not go out to the forests, because they were occupied with their families and did not want to leave them. Each fighter was allowed to take along with him only one family member, and I remember that one of the group instructors, named Moshe Yudke Rudnitzky, faced the dilemma to take his wife or his mother along with him. He took his wife. I, of course, faced no such problem; I was free to decide for myself.

I felt suffocated. Nothing could stop me. I knew that I must get out of the ghetto and join the partisans. I asked to be among the first group that will leave to Naroch, and indeed, I was with this group. We numbered 25 men and women, and this was on the night of September 11, 1943.

The ghetto had a main gate and a few side gates. We tried to leave the evening before, but there was strengthened watch at the gate at the area of Rudnizka and Niemezka streets. To the surprise and disappointment of my friend Senya, I returned home on that night. Going out to the forest wasn't just an act of rescue; the number of fallen in the partisans' fighting was very large. Among them were Jewish partisans, who excelled in heroism and their names and places of burial are not known till this day.

When I departed from my friend Senya, we couldn't imagine which one of us will survive, if at all, he in the ghetto, or me in the forests. When I departed from Senya Rindzunsky, I said to him: "If you survive and reach Eretz Isroel, please convey my regards to my sisters there". Years later, when Senya immigrated in Israel, we visited together our sister Bella and he said to her: "I have regards for you, from your brother Litman". He told her that in front of me, and then we explained to her the reason for this. This was the situation; we were both at death's door. I hoped that if I do not survive, maybe he will. Despite of the fact that, logically, everything seemed lost, we did not accept it, and refused to believe that, indeed, everything is lost.

A few days after I fled the ghetto, a few groups that were better armed escaped to the Rudniki forest and joined the Lithuanian brigade, which was headed by Yurgis (a Lithuanian Jew that was parachuted).

On September 23, 1943, the Vilna ghetto was finally exterminated. On that day, the headquarters and members of the F.P.O, who were still in the ghetto, about a hundred and fifty men and women, left the ghetto through the sewage pipes, with the guidance of Shmulke Kaplinsky, to the Kailis camp and, from there, to the Rudniki forest.

Going out to the forests, through the city and then through the sewage pipes, often aroused anger and bitterness. Every exit required approval bt the headquarters. A selection, between those that would be allowed to go out, and those that would remain in the ghetto, had existed.

Certificate from the Voroshilov Brigade headquarters, of July 21, 1944, Testifying that Muravchick Litman had fought as partisan within the "To Victory" regiment

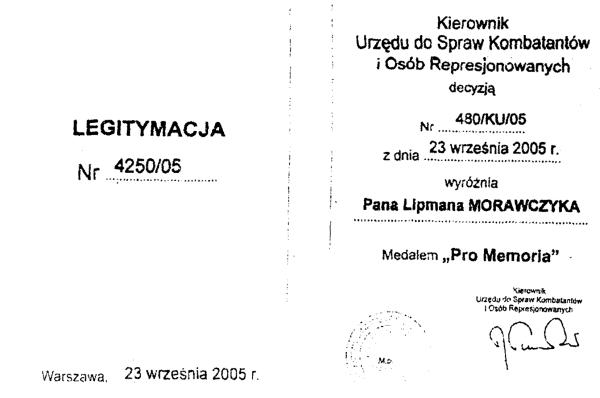

Certificate, that the author was honored with a medal as a fighter of the polish army

Muravchick Litman son of Yehudah, born on 22.3.1917 in David-Horodok in the Pinsk district, nonpartisan, the son of a hired worker, graduated the faculty of chemistry at the Stephan Battori University in Vilna. Did not serve in the army and did not fight at the front. Escaped a concentration camp in Vilna (meaning the Vilna ghetto) on September 1943, and was accepted to the partisans in October 1943.

As of October 9 until December 12, served with a special group, and as of December 12 until April 15, 1944, in the Suvorov regiment within the Voroshilov brigade, was active at the Postav area, Vileika district (Belarus).

As of December 15 until August 12, 1944, servied in the "Pobieda" (victory) regiment in the Naroch Svir area Vileika district. Marital status bachelor. Address: 5, Portova Street, Vilna.

Signed: Litman Muravchick. Date: August 12, 1944.

Para. 15F appraisal: Comrade Muravchick Litman is in the Povida regiment within the Voroshilov brigade. He is a disciplined combatant who fulfills properly the orders. He participated in battles in the Krevichy and Naroch areas.

Took part in railroad battles (attacking trains and exploding railroads). Politically mature. Ethically stable.

Signed: Regiment commander (the regiment) Regiment Comissar.

Verification of signatures - Lt. Colonel.

I left the ghetto at 10 o'clock in the evening of September 11, 1943, with the first group. Two days later, another two F.P.O groups left the ghetto. My group numbered 25 boys and girls. Among them were two adult doctors, a man and a woman, the Dr. Gordon family. I didn't know all the members of the group. Our destination was lake Naroch. We left in couples, through the side gate. Within the ghetto police, there were people who were connected with the underground, and they gave us the keys. Shmulke Kaplinsky was the contact person and he had the key.

I got a pistol from the underground, a Russian revolver, and I took with food for two days. I hid the equipment under my coat. I removed the yellow patch, and we advanced, as gentiles, towards the meeting place: the Jewish cemetery in Zaretche.

My companion was a member of the underground, and as far as I remember, her name was Chume. It was a Sunday night and, for some reason, I feared the local drunks not less than I feared the Germans. Vitka Kempner, who later became Abba Kovner's wife, waited for us nearby the cemetery. The determination to get out of the ghetto was very strong, and this gave me the courage to overcome fear and walk in the streets with a weapon on me. I had no illusion with regards to what might happen to me if we were uncovered. But the urge was so strong - it seems that in a time like this one obtains an additional dose of Adrenalin - and I felt no fear.

Walking in Vilna streets at night, after two years in the ghetto, was a rare vision for me. I didn't feel yet as getting out from slavery into freedom, but I felt relieved. I cannot explain from where did I obtain this optimism.

We gathered in the cemetery amid the graves. In my childhood, I used to be afraid of cemeteries, and would it be normal times, I doubt whether I would agree to lie down amid graves. But this time, I didn't care; all emotions cleared the way to considerations of a different type. The urge to get to the forests gave me strength.

The head of our group, who was supposed to lead us to our destination, was the famous painter Shura Bogen (Kazenelbogen). I got to know him and his wife Ralla (Rachel), ever since the time I studied at the Vilna University, when he was an art student. Our ties tightened in the summer of 1943, when they both arrived from the town Swienzin to Vilna, after the elimination of the ghetto in their town. The majority of the Swienzin ghetto Jews were taken to Ponar for extermination, only a small group of them arrived in the Vilna ghetto, among them Shura, Ralla and Ralla's mother. We called them "the Swienzin group".

With the power of my position at the housing department, it was possible for me to help the family to find lodging in the ghetto. Ralla's mother wanted an apartment with a baking oven, to make it possible for her to bake bread and sell it for making a living.

During the time, we held many conversations. The idea of an uprising in the ghetto, which characterized the youth movements and was the ideological foundation of the F.P.O, was alien to this group. The group intended to leave to the forests. Indeed, my friend Shura with the Swienzin group, headed by Moyshke Shootan, escaped from the ghetto to the Naroch forests.

Swienzin is in the Naroch area. There were already partisans. Their commander was Markov, a Communist, and former schoolteacher in Swienzin. Shura and Ralla knew him personally, as, during the Soviet period, they left Vilna-Lithuania, settled in Swienzin and worked as teachers in the same school where Markov worked. Markov was the teacher of young Jews who arrived from Swienzin, and this acquaintance made the absorption within the partisans easier for them.

The ghetto commander, Gens, began taking measures against the families of those who left the ghetto.

Ralla, Shura's wife, came to me crying and told me "your friend has left me". Out of my many years of acquaintance with both of them, I encouraged her, as I was sure that Shura would return to the ghetto to take her. Indeed this is what happened. Shura returned to the ghetto, after having met with Markov at the brigade headquarters in the forest, and was given an assignment, by Markov, to establish contact with the F.P.O and to encourage leaving the ghetto to the forest.

It must be said that returning from the forest to the ghetto was very dangerous and required courage and determination. Of course, I highly appreciated what Shura did, and regarded it as a sheer partisan act. But, in my eyes, human values that led Shura to return to the ghetto for taking his wife and her mother, and not leave them to their fate, were of no less importance than the partisan assignment.

And back to the track to the forest. It was already two after midnight, when all the couples arrived at the meeting place. About 200 kilometers separated between Naroch and us. The plan was to spend six to seven days for the road, more precisely six to seven nights. We were experienced and knew that taking the road is risky. We were still close to Vilna and were aware that the closer we are to the city, the bigger the risk, since the population in the area was catholic and hostile to Russian partisans in general, and particularly to Jews. At that time, also Polish partisans wandered in the forests, these were linked with the Polish government in exile and were avowed Jew haters, encountering them was very dangerous.

The nights in September are especially long, and till the morning, we had left only a few hours. We had to advance rapidly and cross the railroad near the town of Novo-Vileika. There was a small bridge, guarded by a German unit. We had no choice, and before dawn, we crawled, crossed the railroad, and settled in a small grove adjacent to the railroad, at about 6 to 7 kilometers from the town. We were forced to wait there till the end of the day, to continue our walk in the darkness.

We lay silently in the thicket, and occasionally we heard the voices of shepherds who were wandering just a few meters from us, and luckily didn't notice us, otherwise, our end would have been, undoubtedly, death. When the shepherds went away, we ate some of the supplies that we took along with us from the ghetto; we didn't risk looking for water. At nightfall, we proceeded walking in the northeast direction. The weapons that we had with us were poor; an unassembled machine gun (manual), which we smuggled out of the ghetto in a violin case, and a few pistols, one of them, was mine. Only when we reached the partisans, we realized that such weapons do not allow fighting at all.

Bogen, the leader of our group, was not an experienced guide. Also, he had traveled this road before, under the guidance of Swienzin boys, who as residents of the towns in the area, were familiar with it better than us, city people. At the night of the third day, we advanced about 15 kilometers and, before morning, we hid in the grove. This was a young forest of pine trees, that were not tall but very tangled, and as we lay there, we couldn't be identified. During the light hours, we lay very silent in the thicket and ate the leftovers of the food that we took with us. We had no more food and water and the head of our group, Shura Bogen, realized that we are going astray.

A decision to verify the way to Naroch has been taken. Shura had an Aryan appearance and so had I, we were both young and built up well, therefore he probably chose me to be his deputy, and together we left the group for searching the way to Naroch. Night fell and we wandered in the vast forests, and when we tried to return to the group we lost our way. We continued wandering in the dark, and from minute to minute, our feeling worsened. We failed to find the group and we knew that they are concerned and are wondering whether we lost our way, got arrested, or got killed. Suddenly we saw at a distance the light of a kerosene lamp flickering in the window of an isolated house. Having no other choice, we entered the house. Indeed, we were still close to the city, in the range of danger, but we had no choice, we knew that we must find the group and get away from Vilna as fast as possible.

Since I have never been a partisan before, and never fired a weapon, I did not know how to behave. I knew that in the German and Polish press the partisans are called "bandits". I thought that a partisan should carry a pistol, and so I did.

In the house, we found a couple of peasants and a baby, who stood on the table. I held the pistol in my hand and threatened with it the house owners. The woman got scared and so was the baby who started to cry. The woman bagged for her life. The man kept silent, maybe out of his being scared, or just because being silent is less dangerous than talking. His wife said that he was dumb, but we couldn't know for sure. Anyway, she did all the talking, and I myself was scared. My acquaintance with a pistol was only from the training time in the ghetto. I knew how to assemble and disassemble a pistol, but that was all my military experience. I never held a pistol and never threatened a man with it, and here I find myself in a dramatic and comic situation in which I threaten a baby, a woman, and a dumb peasant. Bogen explained to the woman that we are looking for our friends, and described the place where we left the group. We took the woman and the dumb peasant along with us, seemingly to avoid that after all he would run and turn us in. I will not forget the baby we left alone at home, crying bitterly.

Probably, I used the pistol in an irrational way, but the fact that I pulled it out, turned me, at that situation, into a "partisan". This changed my feeling significantly. My whole attitude towards the Germans had changed the minute I held the weapon. In the ghetto, I felt like a chased animal, and on that night in a tragic-comic situation with a scared woman, a crying baby, and a dumb peasant, I felt, for the first time, as a free man fighting for his life. I knew that this is war, a war for survival, a war against the enemy, and in war like in war "He who stands up to kill you, you kill him first". I was excited and told Shura: "now, if the Germans will kill me, I will know why".

I had no hesitations. I became a partisan, without knowing what it means.

In a cold analysis, my chances of survival, close to Vilna, in a hostile environment, with or without a pistol, were very poor, practically null. But the changr in my feeling was enormous. In the ghetto, I felt like a hunted leaf, and here I am giving the orders, I am my own master.

Eventually, this tragic-comic situation resulted in something good. Before leaving the peasants' house, we equipped ourselves with food and milk for the entire group, as partisans use to do in the forests, and followed the peasant and his wife, until we found our lost group.

Mira Bernstein, a member of the group, asked me whether the peasant gave us to food out of his good will. I did not answer, but was reflecting. Mira was a policewoman in the ghetto economic police. Among other things, the police confiscated money from ghetto inhabitants for public affairs. Anyway, my conscious was clear with regards to the confiscation of the food.

After all the group members have eaten and drank, we began advancing rapidly in the Naroch direction. We feared that if we would be exposed to the peasants, they would hand us over to the Germans. Therefore, we advanced on that night about 10 kilometers by foot, and in the morning, we entered a thick forest and hid between the trees. It was raining all day long, but we retrieved encouragement from the fact that we drew away from the city and are drawing near our destination.

On the fourth night, we mobilized a few peasants with carts, and Ralla's, Shura Bogen's wife's mother, had joined us.

On the seventh day, before morning, we arrived at the partisan area, to the base of Markov's brigade. There I met again with F.P.O friends, who left the ghetto before us, with the Glazman group. I left the ghetto at about two weeks before its elimination. In the forest, there were, at that time, quite numerous Jews: F.P.O groups from the Vilna ghetto, and Jews who succeeded in escaping from ghettos that were setup in adjacent towns. Not all underground members left for Naroch, a major part of the members, including headquarters personnel, left through the sewage pipes to the Rudniki forest.

It is hard to describe in words my feeling as I arrived at the base. I felt a real elation.

The base was in the midst of the forest. The Germans feared to attack the partisans in the forest, and avoided entering the villages Slovoda and Laddy that were adjacent to the base. When we arrived at the base, we already found there a regiment that wholly consisted of Jewish partisans.

The name of this regiment was "Revenge" and, in its majority, consisted of Jews from Kurenietz, Molodechno, Vileika, Sbir, Globoky and more. We came as an organized group and we had a machine gun, some of us had pistols. We were encouraged by the very existence of a Jewish regiment. We were imbued with fighting spirit and hopeful that we will be able to take revenge of the Germans, not just as Soviet partisans but also as a Jewish combat unit.

I joined the companies of Ivan Ivanovitz, a real warrior, and fighter. For the first time in my life, I found myself in a non-Jewish group. Truly, in the university we studied with non-Jewish, but, practically, we did not mingle with them. I didn't have real friends there. It is important for me to point out that, in spite of this fact, one day, still prior to the escape to the forests, a Polish, socialist student arrived, from outside of the ghetto, at my work place, and offered me money and help. Till today I don't know how did he manage to find me, but I cannot forget his brave and rare deed.

So, among the partisans, I found myself, for the first time, in a non-Jewish group and I must admit that I adjusted fast. I knew the Russian language, since at where I was born the gentiles spoke the Belarusian language. I had an Aryan appearance, but I did not want and could not hide my being Jewish, because this opposed the values on which I was brought up. I adjusted quite well to the group among whom I operated.

Our company was given the assignment of confiscating horses for the brigade's needs. We left for the assignment and drew away from the base. Then, after two days, the blockade started. The Germans surrounded the partisan area, and our goal was to stay out of the encircling. Most of the men had no weapons, I had a pistol that sufficed for threatening the peasants but was worthless for fighting the Germans.

The Germans invaded the forest forcefully, an act that they avoided before. They burnt down all the villages and the partisan base, and destroyed everything that they encountered on their way. Those who were able to work, they transferred to Germany for forced labor.

The partisans' tactic was not to go into an open and long battle with the Germans, because of the Germans' superiority in men and arms. Our company tried to find haven in a small island that was surrounded by a marshy swamp. Normally, there was no access to the Island, except in winter, when the swamp froze.

We entered the swamps, and the horses that pulled the cart with food, drowned in the swamp and we couldn't rescue it. I remember that my right leg sank in the swamp, and after I succeeded in pulling it out while applying enormous force, the left leg sank, and so it happened again and again.

On that night I thought to myself - there is talk about horsepower, but the horse drowned because he had no power to pull out his own legs, and man did overcome. With super human force, we managed to arrive at the island. It is hard to understand how did we survive, we were wet and had no food, because it was difficult to carry supplies to the island. The Germans used to apply such blockades approximately twice a year.

About ten years ago, I saw a Russian movie "Go and See", that documents such a German blockade in Belarus, and the evil they did to the population. It was a documentary, with no exaggeration; I found it hard to believe that I, personally, had gone through such an experience.

After ten days, we returned to base. It turned out that the partisan treated the Jews disgracefully, during the blockade. They revealed what they really were - anti-Semites. I wasn't in the base then, but I heard that there were Russian partisans who pulled boots off their comrades, and took their wristwatches and clothing.

The commander, Volodia Shaulevitz, refused to accept the Jews who had no weapons, he also participated in the "looting".

Also, there were those who expressed their hatred of Jews, in this manner: "The gold you handed to the Germans, and here you come to rescue your lives". I couldn't understand the extent of open hatred towards the Jews. Our men were bitter and disappointed - we came to fight and here we encounter a new type of anti-Semitism.

Sometimes, I try to speak in defense of these commanders. There was a blockade, the Germans came with numerous forces, equipped with light and heavy weapons that the partisans did not have. Vilna people and other Jews from the area came to the forest without weapons. At that time, the supply of weapons by means of parachutes was very poor. It was obvious that an addition of people, men and women, without weapons, is a burden for the fighting force. But, from this to abandoning the people without food, without any protection, to forcefully take from them boots, watches and clothing, there is a distance, a very long distance.

Mutual help, between Jews, was great. I should mention Nissan Reznik, who, at this difficult hour, cared for comrades, male and female, most of them girls in a "Zemlanka" (trench) that he constructed.

We were imbued with fighting spirit against the Nazi enemy. We wanted to fight not only for survival, but also for taking revenge of the Germans. We wanted to fight spitefully as Jews within a Jewish regiment. And here it becomes obvious that our idea of forming a fighting Jewish regiment totally opposes the Soviet concept. I remember how Klimov, secretary of the Communist party in our region, who was the dominant authority, explained that the existence of a Jewish regiment is against the policy of solving the nationalities problem in the USSR. We explained our special situation, which differs from other nationalities, and our motives, as Jews, to revenge the Germans for what they did to our families and our people. But the decision was to disperse the regiment between the Russian regiments. A part of F.P.O members, headed by Glazman, left Naroch westwards, in the direction of the Rudniki forests, in the Vilna area, and in a battle with the Germans, all of them got killed, except for one woman that survived.

Our brigade commander was Markov. Following the blockade of 1943, Markov held a selection among the Jews, between those who are suitable for fighting and those who are not. A part of the fighters that arrived without weapons, were organized as a "labor regiment" whose job was to provide services to the fighting regiments.

The suitable for fighting who had weapons, Markov assigned to fighting regiments. I wanted very much to join the fighters, I was in my best years, physically fit, and, indeed, I was assigned by Markov to a regiment which mainly consisted of Russians and Jews, Komsomolsky Otriad (a regiment of the Communist youth movement in the USSR), under the command of the regiment commander Volodia Shaulevitz.

In those days, it was hard to find philo-Semites among the partisans, but I can sincerely say that, relatively to the general atmosphere, Markov was not anti-Semitic.

I possessed a pistol that was given to me by the underground in the ghetto. A pistol was a personal weapon and the commanders desired to have such a weapon. I feared that it will be taken from me, and I will be expelled from the regiment. At that time, the Lithuanian regiment, which consisted mainly of Lithuanian Jews, was instructed to move westwards in the direction of the Rudniki forests, near Vilna. The commanders of this regiment were parachuted from Moscow; among them were a few Jews who concealed the fact that they are Jewish. This regiment had weapons that were parachuted by the free Lithuania government that moved to Moscow, during the war.

I wanted to exchange my pistol with a riffle, but this too required the approval of our commander, Volodia Shaulevitz. Together with Shura Bogen, I approached Volodia and Shura showed him my pistol. The pistol didn't function well; at times, it would get stuck and didn't shoot. We explained to Volodia our wish and, in the midst of the conversation, a shot had sounded, Volodia got hit and fell on the ground. A bullet hit his thigh. Volodia the commander was flown to Moscow and recovered. I met him in Vileika after my release from the partisans. Luckily, this incident happened close to headquarters, Bogen was arrested and brought to Markov. Would this happen at a distance from headquarters, he, undoubtedly, would have been shot; in the forests there was no law and no judge. I got away with the pistol, not before I bribed one of the fighters and gave him my wristwatch.

I was determined to get a riffle. A riffle was something that every one of us longed for. When you had a riffle, you had a chance of being accepted in a fighting regiment, and I wanted it so much. A riffle was a guarantee for life; if you didn't have one, you weren't worth much.

In the forest, adjacent to us, were trenches with Jews hidden in them. These Jews were not fighters. The partisans didn't treat them too well, but we, Jewish partisans maintained contact with them and helped them as much as we could, especially with food supplies. At the beginning of the war, these families hid among the Christian population for a payment, but at a certain stage, they were forced to leave the villages and hide in the forests.

One day, I heard that in one of the trenches there is a Jew, who possesses a riffle. Shimon Zimmerman, from the town Kurinietz, led me to the trenches and I exchanged my pistol with a riffle. But, as I learned later, this was an English riffle with only two bullets in it. I hoped that I will be able to find more bullets, and many of my friends helped me with that. But it was to no avail; we couldn't find even one suitable bullet. The strive to get a riffle was so strong, that it seemed to me that if I get one, I won't let go of it even after my release. By the way, when I arrived in Eretz Isroel, it was the first time that I saw such a riffle in the hands of a ghaffir (supernumerary constable). Only god knows how did such a riffle get to the Naroch forests. Most importantly, I had a riffle.

| Previous | Table of Contents | Next |